This essay has been sitting in my drafts for almost two years. Ultimately, it wasn’t some new found clarity that got me to finish this narrative, but rather a twitter flame war. I keep telling my girlfriend Twitter will come in handy one day, I guess it finally has.

When I joined Unruly in 2016 I did so having developed an interest in learning how successful engineering teams practice Extreme Programming (XP) in the real world. I learned about XP more than a decade prior, when an instructor at my coding bootcamp introduced us to the various forms of agile methodologies that existed at the time. He described XP as “hippies, unicorns and puppy dogs”, an impression I believe he had formed having never seen an actual XP team. When he spoke of XP he seemed to have the mental image of a noisy group of engineers lazilly hanging out all day, trying to wrestle an engineering problem into submission by talking about it. You wont be surprised to hear, I’m sure, that this impression couldn’t be further from the truth, though for the record, his description doesn’t sound like a particularly bad way to spend a day, if you ask me.

When I subsequently left Unruly to join Elastic, I did so with a similar intention - I wanted to learn how a successful remote engineering team operates. I approached this change cautiously aware that I might have to temporarily leave my new-found love for XP practices behind. Almost three years later, I find myself doubting whether I will ever see synchronous practices such as pair programming ever adopted by a distributed company like Elastic.

In hindsight I severly underestimated how wide the gap between these two organisational patterns would be. In fact, in terms of the approach to organisational design, I’d go as far as to describe Unruly and Elastic as diametrically opposed. Lets dig deeper.

Patterns

When humans band together in pursuit of some kind of shared goal they enjoy an endless range of organisational patterns to coalesce around. When a team chooses to adopt one such pattern, they do so because they believe that organising themselves in such a manner will help them achieve this goal. Each pattern encourages different dynamics amongst the members of the organisation, and choosing a pattern is essentially a way of expressing a preference for a the dynamics inherent to that pattern.

It’s a common belief that some patterns work better than others, and that choosing the right pattern is a deciding factor in whether the organisation’s goal is achieved.

I don’t believe the problem of organisational design is as simple as that. As with other complex problems relating to human behaviour, cause and effect are rarely linear, and a pattern that may suit one team, empowering them to become a high-performing team, might be ill-suited to another, causing friction and politics.

In the following essay we’ll take a look at two such patterns, discuss the dynamics encouraged by each one, and finish off with some thoughts on how engineering leaders should think about choosing such patterns.

Two Extremes

If you look at the more radical options on the menu of organisational patterns, you would be hard-pressed to find two patterns more contradictory than the Localised Extreme Programming team, where co-located paired collaboration is demanded, and the Globally Distributed team where physical and temporal freedom are non-negotiable.

I can think of about a dozen different axis by which you could compare different patterns, but if we narrow our view to two aspects, the synchronisation and the localisation of a team, you can clearly see how these two patterns represent seemingly contradictory paradigms with regards to collaboration.

A Localised Extreme Programming team practices the Extreme Programming (XP) agile methodology by co-locating all of the individuals involved in building a product. The software developers, product owners, managers, sales, marketing, business development, and ideally customer, are all based in the same physical working environment. They all participate in regular face-to-face meetings which facilitate their communication, prioritisation, development, and learning activities. This is achieved by setting and enforcing the expectation that colleagues synchronise their physical location and working hours. Team alignment is mostly achieved through synchronous means, such as physical agile boards, daily standup meetings, and hand-written story cards. To be clear, I am not suggesting all XP teams operate in this manner, but rather that this is the organisational pattern we’re discussing .

On the other hand, a Globally Distributed team approaches the process of product building such that they can each collaborate at whatever time, pace and physical location best works for them. This approach relies on teammates adhering to a set of communication principles that ensure effective collaboration, while also freeing them from having to make themselves available to other at a specfic time and place. This freedom enables the organisation to hire the best person for the job, no matter their physical location or timezone. Alignment is achieved through the use of asynchronously and non-ephemeral communication, facilitating the team’s prioritisation and development process. Balance is achieved by ensuring that the team’s entire collaborative process effectively embraces the distributed nature of the team.

Diametrically Opposed

Measured by the aspects of synchronisation and collocation it’s easy to see how these two patterns differ, but why would I refer to them as diametrically opposed? That term would suggest not only that they differ, but that they are actively opposed to one another.

Is that not an exaggeration, you might ask?

Shortly after joining Elastic I began discussing the differences between these two patterns with colleagues across a variety of companies who have adopted them. I quickly noticed a repeating oditty, which would emerge whenever the topic of working practices came up. Discussing the practices favoured by one pattern with the practitioners of the opposite pattern, would often result in what I can only describe as vehement disaproval and dislike.

I describe this as an oditty as these responses seemed out of character for the folks in question. When asking these very same people to consider other, often equally uncommon, patterns they would almost exclusively respond with curiosity. These folks would typicaly demonstrate a hunger for knowledge, and were often searching for new ideas that might allow them tweak and improve their current way of working. They seemed to thrive on new ideas and perspectives, but these two patterns seemed to produce a deeply ingrained aversion to each other.

One such practitioner, a former colleague of mine from Unruly which followed the Localised XP team pattern, seemed very open to trying new ways of working, stating:

We should regularly reflect on our values and our practices to ensure they’re appropriate to our changing context.

Yet when discussing the practices adopted by a Globally Distributed team they exclaimed in disgust:

it's a threat to my sense of self to do things so differently!

I don’t say this to suggest an internal contradiction, but rather to express that no matter how open these practitioners may be to re-evaluating their current organisational design, I consistently found that folks on either side of these two specific patterns naturally seemed to deem the other as inherently contradictory to their own. My anecdotal experience suggests that it would be challenging to find practitioners who would express a clear preference for one without an explicit rejection of the other.

This led me to the realization that the choice of an organisational pattern doesn’t just influence how an organisation operates on the day to day. The choice of a certain pattern can influence how members of the organisation experience their participation in it, and the further a pattern lies from the mainstream, the deeper this influence. This influence dictates the culture that evolves in the organisation, and in turn said culture dictates, or at the very least influences, the talent pool that an organisation gains access to.

A Twitter Flame War

As mentioned above, it was a recent debate on Twitter that led to me finally completing this essay. The debate revolved around the supposed contradiction that exists between these two patterns and their approach to collaboration.

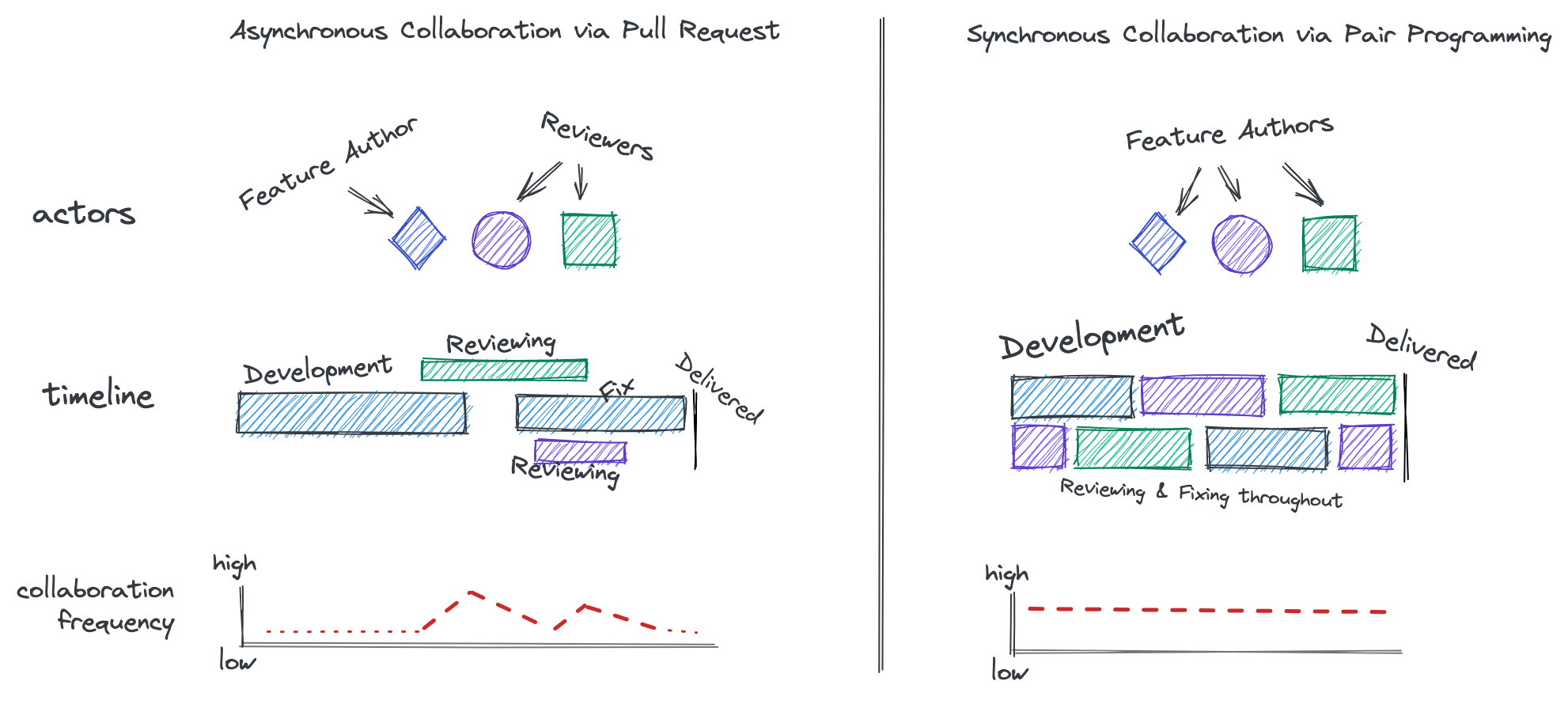

The debate featured dogmatic practitioners of pair programming openly denigrating practitioners of asynchronous practices. What began as a criticism of the impact pull requests have on flow, quickly deteriorated into claims that the practice is harmful and indicative of a lack of trust within a team. Proponents of pull requests were quick to respond by denigrating the practice of pairing, criticising it on both economic and quality grounds.

In all honesty, the whole thing was kind of childish (though it did spark some valuable discussion), but it was further evidence of how divided the practitioners of these two patterns are.

It is truly facinating how emotionally charged this topic has been for folks.

Experiencing Opposing Synchronisation in Development

In my Intentionally Asynchronous essay I explain how Elastic, which has chosen to implement the Globally Distributed team pattern, embraces asynchronous communication. This approach to collaboration is an aspect of the organisational pattern that Elastic has chosen to enforce. This choice places Elastic at a far end of the synchronisation scale. The Asynchronous end.

On the opposite end we find Unruly, as adopting the Localised XP team pattern means that entirely synchronous practices, such as pair programming, are actively enforced by the team. Pairing, a practice encouraging constant communication between teammates, is purposefully intended to dial up the feedback loop between the different team members. Designed to improve on the more traditional work environment where direct communication is often discouraged outside of perscribed interuption points (such as the lunch break, team meetings and agile ceremonies such as Daily Standup), XP has the effect of synchronising not only the developmen practice, but also other ancillary practices. For example, design discussions, impediment identification, or the analysis of feedback neccessery for a team to reevaulate, or even pivot on, requirements are all synchronous activites undertaken by the team in pairs.

We can see how different the developement experience would be for an engineer at Elastic relative to Unruly.

An engineer at Elastic goes through the development process via a series of asynchronous interactions with their teammates. Though they might tackle some of the more challenging collaboration efforts over a synchronous video call (ideally recorded and documented), the majority of the process will likely have taken place through written communciation on a shared document or Github issue. Once the details are ironed out, an engineer would likey write the code, submit a pull request with the specified enhancements, and notify their teammates that their work is ready for review. The reviews will likelly lead to some collaboration in the form of rethinking and reworking the problem, but hopefully the code is ready shortly there after, and deployed to production.

At Unruly, on the other hand, the entire process would be handled by a pair. An engineer would sit down with a product manager and designer, writing a story card which specifies the requirements, and place the card on the team’s agile board. A different pair of engineers would then pick up the card and begin implementing the enhancement together. Assuming the work spans more than a single day, pair negotiation would take place at the next morning’s daily standup meeting. This means that a fresh engineer pairs up with one of the engineers from the day prior. This new pair will then get back to work on the story, with the new engineer providing a fresh perspective, and the other providing context into the work done the day before. This cycle repeats until the work is complete. As a review is natuarally taking place throughout the development process, there is no need to add a separate review phase, and the enhancement is deployed immediately.

The process followed by the Globally Distributed Team enables engineers to work autonomously, at their own pace, with complete freedom to fit work around their lives, rather than the other way around. That said, feedback and collaboration can be slow, easily leading to a high rate of rework, which is often a source of pain for engineers and impacts the rate and quality of delivery.

The opposite process, as implemented by the Localised XP Team, greatly improves the feedback cycles enabling richer collaboration. Alignment is often easier, so is mentorship and quality assurance, but this comes at a cost to work-life balance and suffers from increased friction between the practitioners. In an environment where teammates are encouraged, and arguably forced, to pair throughout the entire day, you find that teammates are communicating far more than usual. Not only when compared to a traditional workplace, but even when compared to what they would consider the norm in their personal lives.

It’s easy to see how, from the perspective of an engineer on the team, the experience differs greatly.

An Imbalanced System

If you think of an organisation as a system, then we can describe the influence of a chosen organisational pattern as a variety of forces. These forces create feedback loops inside the system to which teammmates naturally respond, whether consciously or not.

For example, the seemingly slower pace of communication on a Globally Distributed Team can create a feedback cycle that encourages engineers to work on several tasks in parallel, otherwise they might sit idle for hours waiting on a reply from a teammate. Similarly, the constant pairing on the Localized XP Team discourages individuals from experimenting or independently exploring ideas as they may fear their pair’s watchful eye and scrutiny.

We can see how the differing experience felt by an engineer in either organisation is the result of these feedback cycles, and how these can be tied explicitly to the company’s choice of organisational pattern. This might seem an obvious conclusion to make, but ask yourselves whether you conciously think about these forces and how they affect your own teams. I don’t think leadership is often intentional enough in tackling these forces, rarely recognising their existence, let alone the implications of the imbalanced system they create.

What I mean by imbalanced is that the pattern produces forces that differs in some way from those produced by more mainstream patterns. As a result teammates may find themselves in new and unfamiliar territory, and it’s up to the organisation to compensate for this by providing some kind of system fix, as individuals may not have a best practice to lean on.

If we compare our two patterns against most engineering organisations, it’s easy to see how these feedback cycles differ from the mainstream. Though it isn’t unusual for engineers to find themselves blocked, they usually work in similar timezones as their teammates and are able to unblock themselves by reaching out to each other synchronously. Similarly, though it isn’t unusual for engineers to fear a teammate’s scruitiny, they can usully experiment and iterate privately, prior to receiving feedback.

So how do we correct these imbalances? It’s important to keep in mind that if an obvious system fix were available, it would have been baked into the pattern long ago. Fixing such an imbalance will always have to be tailored to the specific team, and the individuals in it, that said I think it’s worth exploring specificly how Unruly and Elastic have gone about correcting theirs.

Imbalanced by Extreme Programming

My former CTO at Unruly, Steve Hayes, once told me that when Kent Beck first named Extreme Programming he was trying to be divisive and force the conversation about it. I’m not sure whether this naming choice was helpful or harmful, but there’s no doubt that XP encourages more interpersonal tension in a team than you might expect to experience in a more traditional work environment.

It isn’t unusual for teams who practice pair programming to spend 8 hours a day talking. In fact, it’s encouraged. All work is performed in pairs, or on some teams ensembles, whether it’s writing code, making design changes or writing marketing strategy, everything is paired on. XP consists of many more practices, such as Test Driven Development, Continuous Integration and Delivery, and short iterations, all of whom represent the “extreme” version of the mltitude of software engineering practices advocated for by the agile community According to practitioners, it’s precisely this extreme approach that make XP so appealing - it enforces the shortest feedback cycles across all practices, which in turn, enables them to produce their best work.

But the problem with all extremes is that, by their very nature, they defy the status-quo and for many people this introduces understandable challenges.

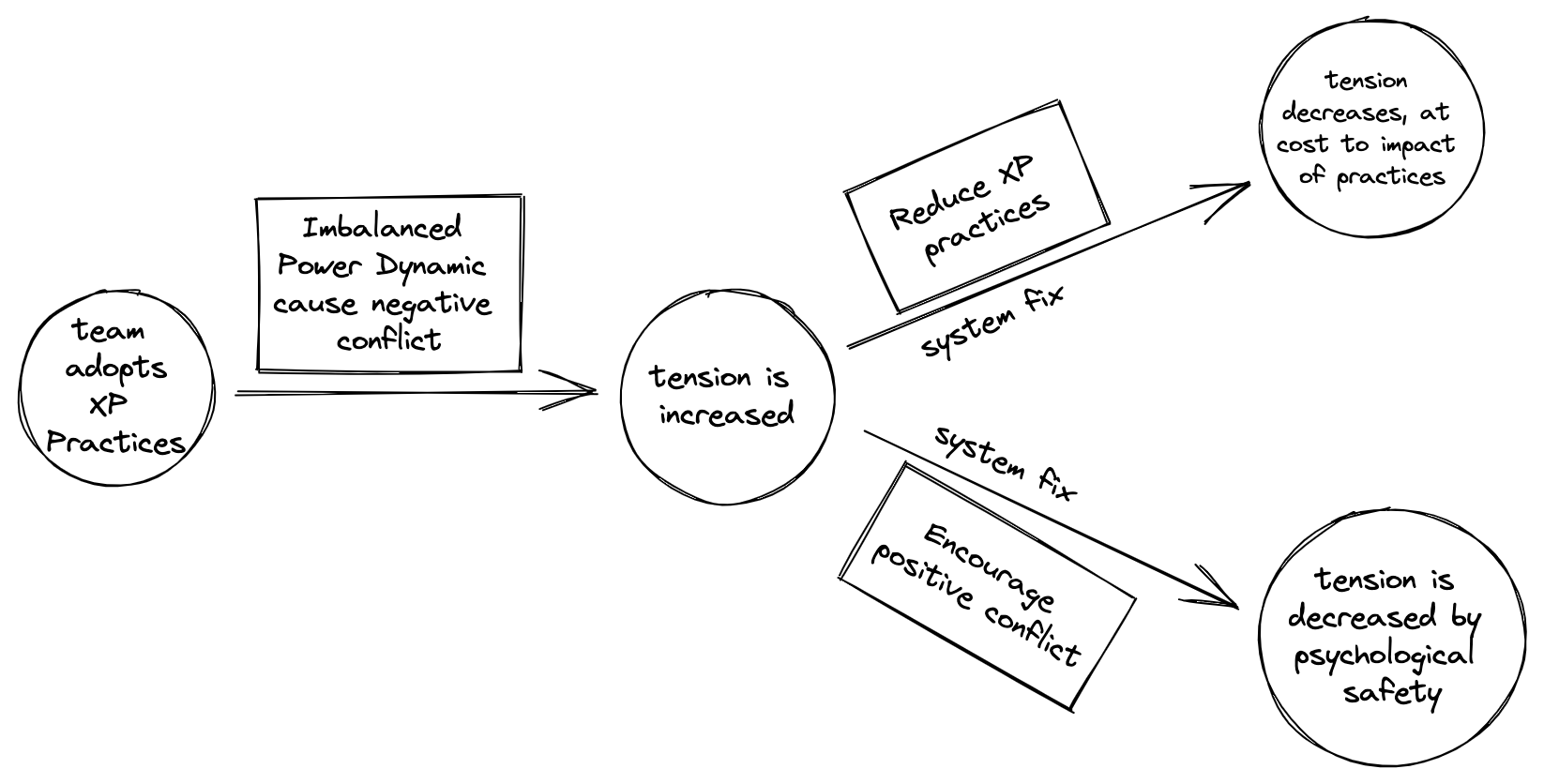

Dialing up the communication in a team inevitably exacerbates interpersonal conflict, such as those caused by imbalanced power dynamics between individuals, a problem eloquently described by Sarah Mei on a number of occasions.

We touched on these challenges when we disucssed our Feedback & Cake and Pairing checklist practices, but the bottom line is this: pairing is emotionally taxing, exasperates both intrinsic and extrinsic power dynamics and enforces strict working hours and cohabitation (whether side-by-side or over zoom).

These challenges are the primary source of tension inherent to Localised Extreme Programming teams, and based on my observations of teams practicing XP, addressing them appears to be a prerequisite to becoming a high performing XP team.

The daunting thing, though, is that addressing these challenges is hard. Emotions are a difficult things to address, and it requires attention to, and investment in, things that aren’t always highest on a team’s list of priorities. That said, when my Unruly team and I decided that we had to tackle these problems and prioritised the effort to do so, we made incredible progress. We came up with a list of practices, which I covered at the time in a dedicated series of essays, that enabled us to address many of the tensions caused by XP.

Discussing these challenges with teams from other organizations, I found a repeating pattern where teams actively took measures to address these tensions by either reducing the scope of XP practices (for example, by introducing a mix of both paired and non-paired work) or by introducing practices that incentivise positive interpersonal conflict in order to better prepare teamates to handle the negative conflict which is bound to arise. The former would most likely work, but makes it harder to intorduce change and change practices in the future, as teamamtes learn to associate change with tension. The latter encourages a resiliency to change and enables a team to pursue excellence through continuous improvement.

My main takeaway was that in order to address the imbalance introuced by the Localised XP team pattern, active steps had to be taken to improve psychological safety and encourage positive conflict. While this is a worth while exercise for all teams, whether or not they practice XP, both the neccessity and the return on investment are far higher for XP teams, such is the imbalance in the system.

Imbalanced by Distribution

The imbalance caused by global distribution is more intuitive than that caused by XP, though in many ways far more nuanced.

It’s fairly intuititive that the further away a person is, the harder it is to collaborate with them. Out of sight, out of mind, as they say. Fear of this precise tension is what has held many companies back from embracing remote work for years.

Few leaders in the industry were prepared for the prospect of a global pandemic forcing them to pivot into a remote-first company. That, though, is precisely what happened in 2020 and the transformation was swift. The vast majority of engineering teams transplanted their working practices in a wholesale manner, discovering to their surprise that not much has changed. Most of their practices still worked; teams continued to deliver work much as they did before, and collaboration continued to take place in the same dedicated meetings, just that instead of doing so in-person they shifted Zoom.

This wouldn’t last long though. Small cracks appeared as individuals began to feel detached from their team. They began to notice decisions being made that they were unaware of until long after they took place, and felt frustrated by the distance they now feel from their colleagues. Folks began to complain about a loss of serendipitous moments of collaboration, often referred to as water-cooler moments, a tension caused by their move to remote work that they were not prepared for.

This is where the nuance comes into play - teams often find the shift to remote fairly straight-forward as the default for the majority of teams, co-located or otherwise, is to embrace independent work and asynchronous practices such as pull request. As mentioned above, distributed teams lean heavily on asynchronous practices to collaborate and maintain alignment, and it turns out that many of the practices employed by such teams are already the default for many co-located teams. At first glance, the shift from co-located to remote seems minor, as the team’s working practices don’t neccessrily have to change much. It’s only when you practice remote work for a while, or dial it up by hiring across timezones and becoming distributed, that the tensions build up and cracks begin to show.

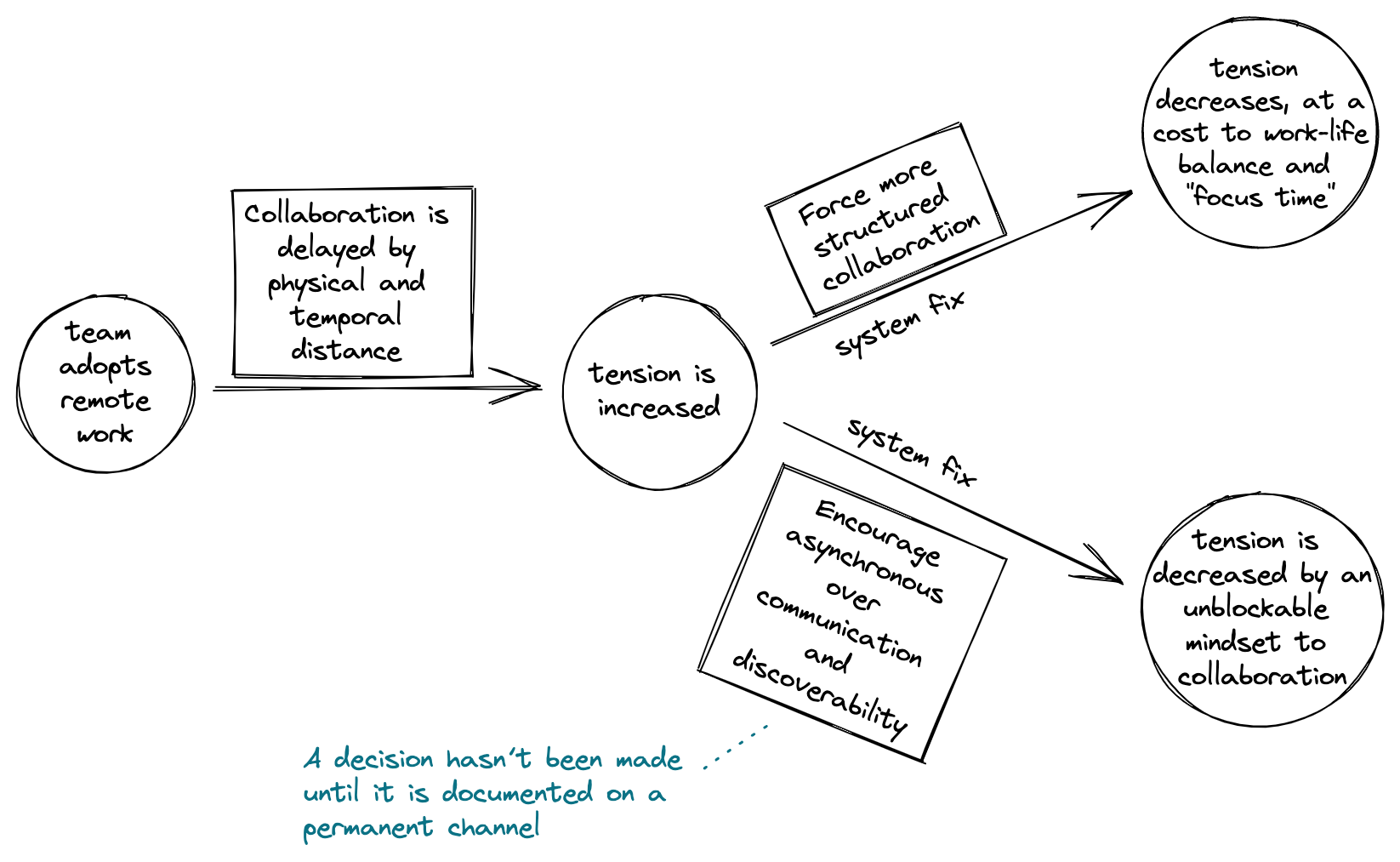

In a recent essay we explored the distinction between remote and distributed, a key takeaway of which was that any tension caused by the adoption of remote work tends to have a greater impact on distributed teams. The greater the distribution, the greater the impact. The loss of unplanned, out of band, moments of collaboration is bad enough for remote teams, but for distributed teams this loss is far greater, as jumping on zoom is far harder when you only have an hour of overlap with your teammates. This tension is exacerbated further by the fact that structured collaboration, such as Daily Standups are equally impacted, meaning that even mainstream ceremonies are hard, or impossible, to rely on.

Remote teams tend to lean towards a synchronous system fix, by enforcing a higher degree of structured collaboration than they would have done had they been co-located. Many engineering teams fell into this trap during the pandemic, and I’ve heard many folks lamenting the amount of meetings that have creeped further into their calendars over the past two year. Distributed teams, on the other hand, apply the opposite system fix, doubling down on asynchronous practices, extending them across most of their collaborative process, and enforcing these practices by ensuring that decision making is no longer blocked by synchronous practices such as meetings.

Elastic addressess these tensions by embracing an intentionally asynchronous culture. This too was covered in depth in a dedicated essay, obviously titled, Intentionally Asynchronous, but it’s worth calling out the guiding rule: A decision hasn’t been made until it is docummented on a permanent channel. The goal of this edict is to encourage over-communication by asynchronous means, ensuring a chain of archived context, which in turn rebalances the system by making unstructured collaboration an integral part of teammate’s day.

This is where becoming intentionally asynchronous elavates from being an recommendation, to becoming a neccessary system fix designed to address the tensions caused by distribution.

Thinking about Imbalanced Systems

You may be thinking, having covered these two extremes, that this essay is a sort of clip show essay, designed to link you to a bunch of essays I’ve written before. It’s actually the other way around - I began writing this essay and realised that I had too much to say. I couldn’t fit this into a single essay, so I exploded the content across a half dozen essays.

If you take one point away from this entire effort, it should be this one: Your organisation is a system, and systems are governed by forces. Identifying the forces that impede your team’s process enables you to identify and apply the appropriate system fix. Your goal in doing so is to drive the team towards becoming a high-performing team.

Look for the force that causes an imbalance in your system, and then rebalance it. The closer you are to mainstream practices, the easier it is to rebalance, but be careful when choosing your system fix. Most teams are not high-performing teams, and aligning with the mainstream can come at a cost in that regard. The hard part is knowing which system fix will enable your team to become high-performing, and which will get in their way.

When I discussed this perspective with a former colleague, she phrased it better than I ever could:

When I see a people problem I'm like bring it on bitch

This is the fun part about engineering management… it’s just another complicated distributed systems problem.

As much of a cesspool of disinformation and racism as Twitter tends to be, I still believe it provides a wonderful breeding ground for ideas and discourse.

When the pandemic kicked off in 2020 I saw many companies who practice XP transition into a remote first reality. As a result, many are no longer co-llocated at all and have found ways of adapting their XP practices to a remote environment.

An Ensemble is where three people, or more, are involved in the practice of developing or designing a feature. This is also known as a mob though I dislike that term.

These challenges are also the reason why Extreme Programming teams often suffer from a lack of diversity. This isn’t an inevitable consequence of XP, as teams who have made the effort of addressing these challenges often find, but it’s hard work and requires an intentional effort.

This is why folks often conflate the debate on localisation (Distributed vs. Co-Located) with the debate on Synchronisation (Sync vs. Async). A former colleague of mine made the same observation recently, tweeting a nice visualisation of this.