Psychological safety is undeniably important in every team, but it wasn’t until I joined Unruly, where we practice Extreme Programming, that I felt like psychological safety is essential for me to both produce good work as an individual and to stay mentally healthy.

In case you’re unfamiliar with Pair Programming, I’ll explain that the idea behind the practice is that it represents the extreme form of performing a Code Review. Instead of creating an asynchronous process in which a developer submits a piece of code she has written to review by a second developer, we pair the two developer together and ask them to write this code together.

Pairing is not a mentoring session or a division where one person is coding and the other is watching. Pairing is a collaborative process where both sides take part in a dialogue about the design, implementation and integration of a piece of code.

As I’ve mentioned in past posts, research has shown us that the trust is a key ingredient to fostering effective collaboration in a team. From this, I believe, we can infer that when your coding process is a collaborative one, trust plays a decisive role in whether you coding process is successful. In fact, we could further infer than it does so to a higher degree than it would in an environment where collaboration is a less defining aspect of the practice of coding.

This post is part of the series The secret sauce to an effective team which describes the steps taken within my team at Unruly in order to facilitate the fostering of psychological safety amongst members of the team.

The Detriment of Distrust to Coding Practices

In more traditional technical teams I have often been able to shut the world out of my work. In fact, I’d say that to many developers, that ability is considered a prerequisite to choosing a working environment.

What I mean by that that is that many developers feel that in order to be effective they need to be able to isolate themselves from their environment. Be it by means of noise canceling headphones, working from home or hiding behind a wall of monitors, their ability to enter the ephemeral and elusive zone is a prerequisite to doing good work.

In such an environment, by definition, other people are a detriment to achieving good work, and so while interpersonal challenges are identified as a detriment to effective team work, they seem to be less recognised as a detriment to the coding practice itself.

My personal take on this is that the separation of interpersonal challenges from the challenge of product delivery is actually harmful to the mental health of a team. By separating the two, we’re disincentivising individuals from raising such conflicts as issues to be addressed, as they are seen as less relevant to the work at hand. This topic as well entirely deserves its own post, so I won’t delve into it now, but I would like to express that my feeling is that traditional coding practices often incentivise not just the siloing of knowledge, but the siloing of feelings too, and we all know what happens when we bottle up stressful emotions. The corks burst.

In Pair Programming

In contrast, in a paired environment, the very act of coding relies on having positive and effective relationships with your teammates. If an individual in the team insists on working in Vim and another individual has only ever worked in an IDE, then this gap will have to be bridged before these two individual can work as an effective pair.

Bridging such gaps requires trust between individuals, as both individuals must feel comfortable enough to challenge each other’s assumptions and preferences along the way.

This is true not only for the working environment but also for the work product itself. When there exists a lack of trust, it is harder for one developer to challenge the decision of another in regards to, for example, the use of one code construct over another. This is often exasperated by an imbalance of power between the individuals. It’s hard enough for a newcomer to challenge an experienced developer under traditional circumstances, but in a paired environment where feedback has to be immediate and face-to-face, this is often for more challenging.

In a Paired environment, failing to address conflict in a team can easily lead to the breakdown of the entire process, and so, encouraging a culture of feedback has been a paramount priority to us.

Setting a Foundation

In my team we have been experimenting with a variety of tools designed to reduce the barriers to immediate feedback. In a previous post I talked about Feedback & Cake, which is designed to foster an overall feeling of comfort around giving and receiving feedback amongst colleagues. In this post I want to introduce you to our Pairing Checklist.

A culture of feedback is good for course correction along the way, but an equally important foundation is the prescription of a mechanism for setting mutual expectations prior to taking any action which might have required a course correction later.

In a team meeting in which we discussed the practice of pairing, we tried to identify the behaviours we felt were most conducive to an effective and positive pairing session. We found that there exists a variety of pairing practices which were open to discussion and interpretation. Many of these practices were contradictory, yet subjectively all were reasonable and as a result, could potentially lead to a Pair being ineffective due to conflicting preferences.

After discussion we came to the conclusion that conflicting preferences can always be compromised on within a pair, but a fear existed that due to power dynamics between the individuals, the discussion might never actually take place. Instead what would happen is that the more powerful individual would simply force the pair into their preferred method by default.

Forcing the Conversation

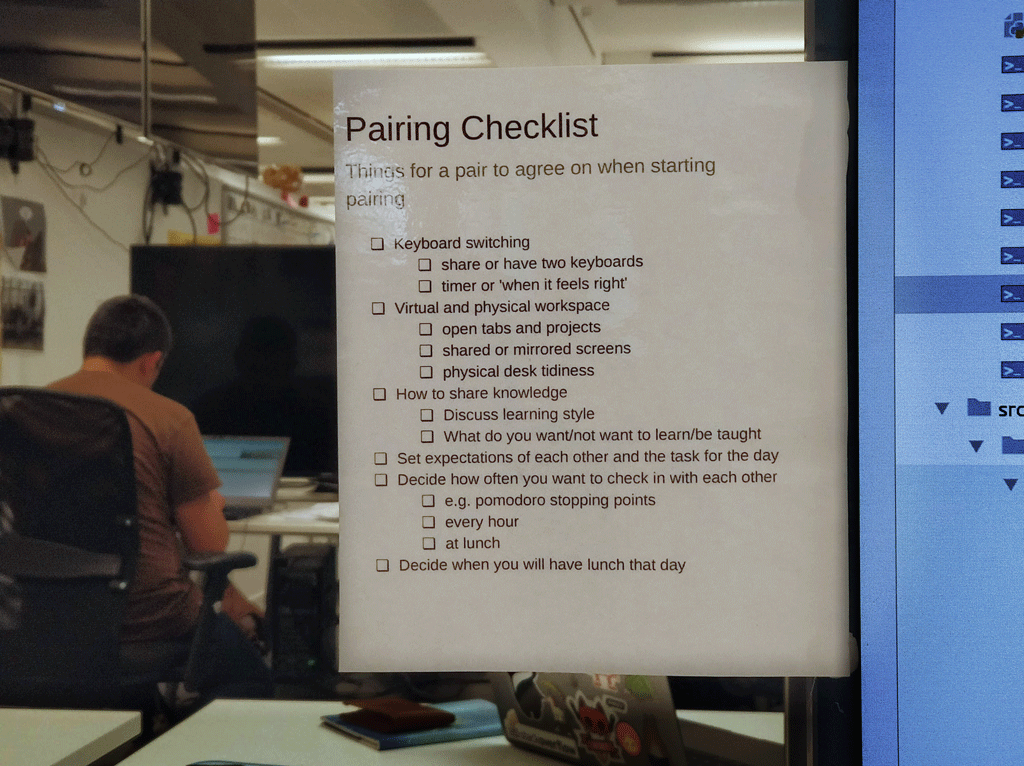

If you walk into my team’s area in the Product Development department at Unruly, you’ll spot a checklist protruding off of every workstation.

Whenever a pair sits down at a workstation to begin work, they look at the checklist and run through each of the items on it. The checklist covers the different options they might need to agree on before beginning a pairing session.

Not every item on the list is relevant to every pairing session. As the work we do is varied, so are the practices the pair must choose between.

In the photo above you can see the checklist as it is currently phrased within the team, but reading through it for this post I realised how specific it is to our terminology. Bellow I rephrase some of the items on the checklist to make it a little more generic, self-explanatory and usable to other companies.

The Pairing Checklist

The following is a verbose version of the checklist intended to clarify the meaning of each item.

Things for a pair to agree on when starting pairing

Physical workspace what the physical workspace feels like

- Are you happy with the tidiness of the desk?

Virtual Workspace what the virtual workspace feels like

- Do you prefer a single open project at a time, or should we open all relevant projects at once?

- Should we keep the browser tabs from a previous session or should we close everything and start from scratch?

- Would you prefer we share a single monitor or should we switch to a workstation with dual mirrored monitors?

Keyboard Switching how the pair uses the keyboard and prefers to control ho’s typing at any given time

- Would you prefer to use a single keyboard which we pass between us or should we each have our own keyboard?

- When would you prefer to switch between driving (typing on the keyboard) and navigating (not typing)?

- Using a timer with a set rotation time (usually 10 minutes each)

- Using the TDD cycle (the first person writes a test, the second writes the implementation which makes the test pass then writes the next test, and we switch again)

- When it ‘feels right’ to switch (we recommend this only happens when the pair is experienced at working together.)

Knowledge Sharing when a knowledge gap exists between the individuals in the air, how should knowledge be disseminated

- How would the person with less knowledge like the knowledge to be introduced? For example: whiteboard explanations? or running through the code? or perhaps over coffee?

- How much would the person want to be taught? Only things specific to the story? or perhaps broader overview of the system as a whole? or deeper into language and tech specific details?

Goal what’s our goal for the session

- Keeping in mind how much time we have, the scope of the story and the team objectives, what would you expect us to achieve today? This helps keep the pair focused and realistic about what is possible to achieve in the session.

Checking In depending on whether we’re actively pairing, or splitting a task etween the pair, we might want to make sure we “check in” with each other along the way.

- When pairing on code - When do we want take breaks? Would you like to use Pomodoro? or perhaps every few commit points? etc.

- When splitting a task between a pair (such as when researching a new topic), when would you like to check-in and compare notes? Every hour? By the lunch break? etc.

Lunch

- And while we’re on the topic of lunch, when would you like to take the lunch break?better to agree on this when starting a long day rather than debate it half way through the session.

Summary

Feel free to amend our checklist to fit your team’s culture and assumptions, but try and keep enough flexibility in the checklist to allow each pair to use it without feeling constrained.

The goal is to ensure that subjective decisions are made together, rather than defaulting to whatever the more powerful voice in a pair might prefer. This is important in order to allow teams to develop a stronger culture of feedback, positive decision making and compromise.

The interesting thing about little nudges like the Pairing Checklist is that they only work when the team already has a culture of trust and feedback, but once they are in place they actually work to reinforce this culture and strengthen it, so while trust is a prerequisite, it actually is improved by introducing these practices. It’s a two way street.

Print Me

Bellow you will find a printable version with the more concise wording of the above checklist.

- In fact, we're not necessarily discussing code, but that distinction is better left for a broader post on the topic of Pair Programming

- The subject of power dynamics in a pair is, again, a subject for a far more in-depth post, but I felt it was worth pointing it out here, as they are the root cause of many trust issues you might encounter in a pair.