In the first part of this essay, we covered what we mean by asynchronous communication, and I introduced you to the two tools that Elastic uses to set the baseline for, and align on, the expectations we have of our distributed teams.

Your continued interest in the topic of Distributed by Design suggests you’re, at the very least, intrigued by the possibility of asynchronous work, but you might not be entirely sold on the merits. Given the challenges inherent to asynchronous work, I couldn’t blame anyone for doubting whether the return justifies the effort, especially if your team is not distributed, but rather merely remote.

I don’t personally believe everyone is well suited for asynchronous work or distributed teams. In fact, I think it’s a minority of people who are. That said, I also believe this is a large enough subset of the industry that those companies tackling this challenge well will easily find themselves able to grow their high-performing teams.

This post is part of the Distributed by Design essay, which begins with Remote isn’t Distributed, describing what I learned over two and a half years as an individual contributer and manager on a distributed team at Elastic.

Part II: A Chain of Archived Context

Lets explore what I believe to be an immediate and tangible benefit inherent to asynchronous work: something I call the chain of archived context. While there are other arguably more valuable benefits (such as a healthier work-life balance and inclusivity), it is this chain that gave me my first aha-moment regarding asynchronous communication.

The Challenge

One of the problems I’ve struggled with throughout my career, at every single company (Elastic included), is remembering why we made a decision at some point in the past.

Remembering why we made a certain decision in the past empowers us to make better-informed decisions in the present, and even though I’m generally far more interested in talking about where we’re going, rather than where we’ve been, changing a decision is always safer when you understand why that decision was made in the first place.

In Relation to Documenting Working Agreements

A common allegory for the importance of remembering why is the parable of the five monkey experiment, which describes how a group of individuals can easily end up following a certain rule without knowing why it is that they follow it.

I’ve seen this happen first hand in many engineering teams, where the team follows a certain practice because that’s how it’s always been done.

At some point the team made a decision such as limitting themselves to no more than one automated end-to-end test per component, in order to keep the duration of their tests on CI as low as possible. Years have passed and the team finds itself in an unfortunate state. Each of their UI components has ended up with dozens of test-cases baked into a single unmaintainable, error-prone, and unreliable, automated test. The team had agreed to follow this rule years ago, documented it on their official working agreements wiki page, and even added a linting rule that verified this behaviour. They created an environment that actively encourages every new joiner on the team to fall in line, follow the rule, and even enforce the rule whenever they see a teammate fail to follow it.

What the team had forgotten was that this decision, made in the early days of the company, was the result of a limited budget on their CI server. They could only afford to run a certain amount of tests per month, and to avoid running out of budget chose to optimise for CI server resources, at the expense of test maintainability and quality.

This decision made sense at the time, but now, years later, the company no longer had this budget problem. In fact, they had moved to a completely different CI system, where they had no limits whatsoever. The team continued to follow a rule that was no longer relevant, but none of them realised, as they had forgotten why they had set it in the first place.

The question is, how do you retain this knowledge, and how do you make it discoverable?

In Relation to Documenting Technical Decisions

As engineers, we are notoriously bad at documenting technical decisions, and though this topic is far from under-discussed, I find we tend to focus on architectural decisions rather than the ad-hoc technical discussions and decisions made in the day-to-day.

It’s my anecdotal experience that we focus on the larger architectural decisions, not only because we consider these decisions more impactful, but because it’s the path of least resistance.

In a typical engineering environment, technical decisions are made in synchronous meetings and conversations, often followed up by the actual implementation of the decision. If documentation takes place at all, it usually happens after the definition of done has been achieved, at which point, lets be honest, most engineers want nothing more than to move on to the next problem, and the quality of documentation suffers accordingly.

There’s a high degree of effort associated with slowing down in order to document decisions that were made days, weeks, or even months ago. This effort, perceived or otherwise, only grows as you go beyond the decision itself to explore the context and conversations that led to it being made.

I find it’s easier to convince engineers that incurring this effort will pay off when discussing architectural decisions, as these tend to be bigger, more visible, and more likely to get questioned at some point in the future. But when it comes to the smaller decisions, that we tend to make every day, this effort is deemed too high.

As engineering leaders we have struggled with this for years, which is why for the most part we advocate for solutions at that level (such as Architecture Decision Records [ADRs], of which I’m a big advocate) and then, following the path of least resistance, we call it a day.

It’s worth noting though, that even when an organisation successfully adopts ADRs, they might communicate the decision and why it was made, but rarely will it include a broader context. Valuable context such as the broader conversation that took place concerns voiced by teammates, alternate options, or alternate priorities, all tend to get lost to the ether.

This is reasonable, as ADRs are meant to be easy to consume, and documenting too much context would make this harder and less useful.

The question is, how do you make it easier to document decisions sooner? Perhaps even as they’re being made?

And how do we include the broader context without documentation becoming too much of an effort to consume?

The Aha-Moment: Documenting the Broader Context

A year or so into my time as a member of a distributed team I had a true aha-moment.

Historically I have found both of the challenges above hard to tackle. I often found that I was missing the broader context when I needed it. In hindsight, this makes sense, as documenting these things is generally hard. As mentioned above, most of this context existed as in-person, perhaps as watercooler conversations, or spread out across multiple different face-to-face meetings.

This is a lot of content, yet good documentation needs to be searchable and easily consumed, which means it has to be concise. Including this sort of context would actually defeat the purpose of most documentation efforts.

This means, I realised, that documenting the broader context has to exist separately, and in addition, to the documentation of the actual decision, and it likely requires a richer media format than what a text file, such as an ADR, is able to deliver.

Do you see where I’m going with this yet?

As a Distributed Team this is Easier

The difference for teams who practice asynchronous communication is that, unlike any co-located team I have ever been on, this broader context is actually straightforward to document.

Conversations are always documented in an Email thread, a Github issue, or, if a burst of synchronous collaboration is required, a Zoom call.

Whichever medium we choose, all this context is not only easy (and cheap) to record, but also to link with the source of truth. What I mean by source of truth is a place where a future teammate (or a future self) is most likely to go looking for answers when they have questions.

By linking the broader context to the source of truth we can create a chain.

A Chain of Archived Context.

Lets take a closer look at two examples for how this works.

Example I: Working Agreements

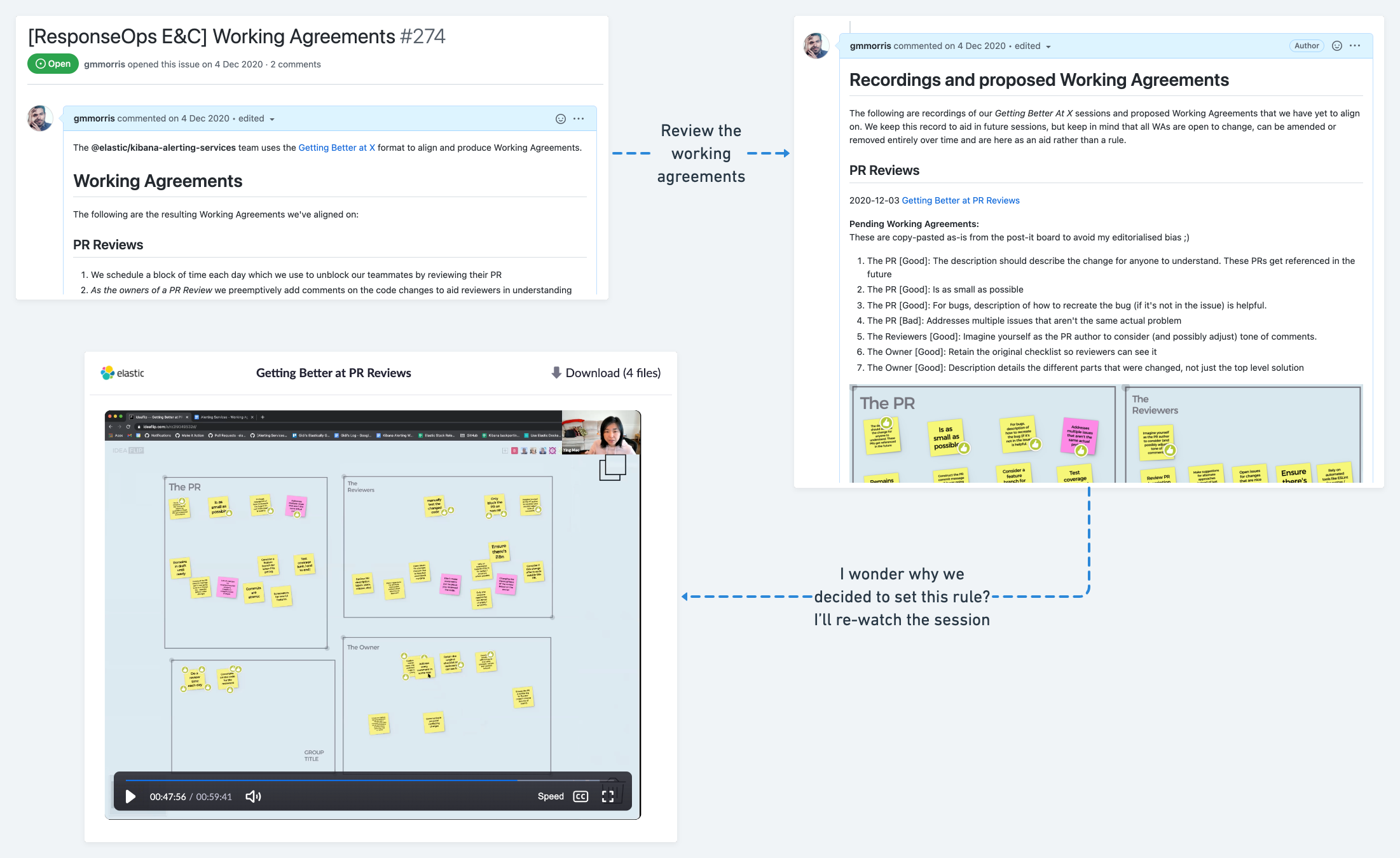

One of the practices I carried over from Unruly to Elastic is our Getting Better At X sessions. Every once in a while my teams get together to discuss a specific practice, such as PR Reviews or Automated Testing, and spend a concentrated synchronous hour tackling the question: “How can we get better at this practice?”.

At the end of every such session the team refresh their working agreements, which reside in a dedicated Github Issue, documenting the decisions made on the session and linking this decision to a recording of the discussion.

The archive aspect comes into play the moment a teammate asks: “why do we do this thing we’ve always done?”. As an engineering manager I find this happens quite often in one-to-one coaching sessions, or team meetings.

Whenever I’m asked this question, I point them at the Working Agreements issue, and suggest they go back to the recording of the relevant Getting Better At session, and find out. If they feel the reasoning is no longer valid, I suggest they bring it up with the team, and revisit the agreement.

I found this much harder back at Unruly. Infact, the only reason it was even possible was thanks to a handful of collegial old-timers, who had remained at the company for years, and were available to answer these questions - assuming they recalled the reasoning themselves.

One such colleague, benji, made the same observation when he left Unruly, interestingly commenting on the fact that some teams were in-fact archiving their stand-up meetings by recording them, but no one was actively consuming these recordings. In hindsight Benji’s observation was a missed learning opportunity on my part. Though I had taken note of the unnecessary need for recording those meetings, I entirely missed the fact that the real problem was the lack of discoverability of these recordings. Recordings are only useful if they are archived in a discoverable manner. This is why linking the recordings to the source of truth, where the decision has been documented, is critical.

Example II: Technical Implementation

(Or Why the F**k Did I Do It That Way?)

We’ve all been there.

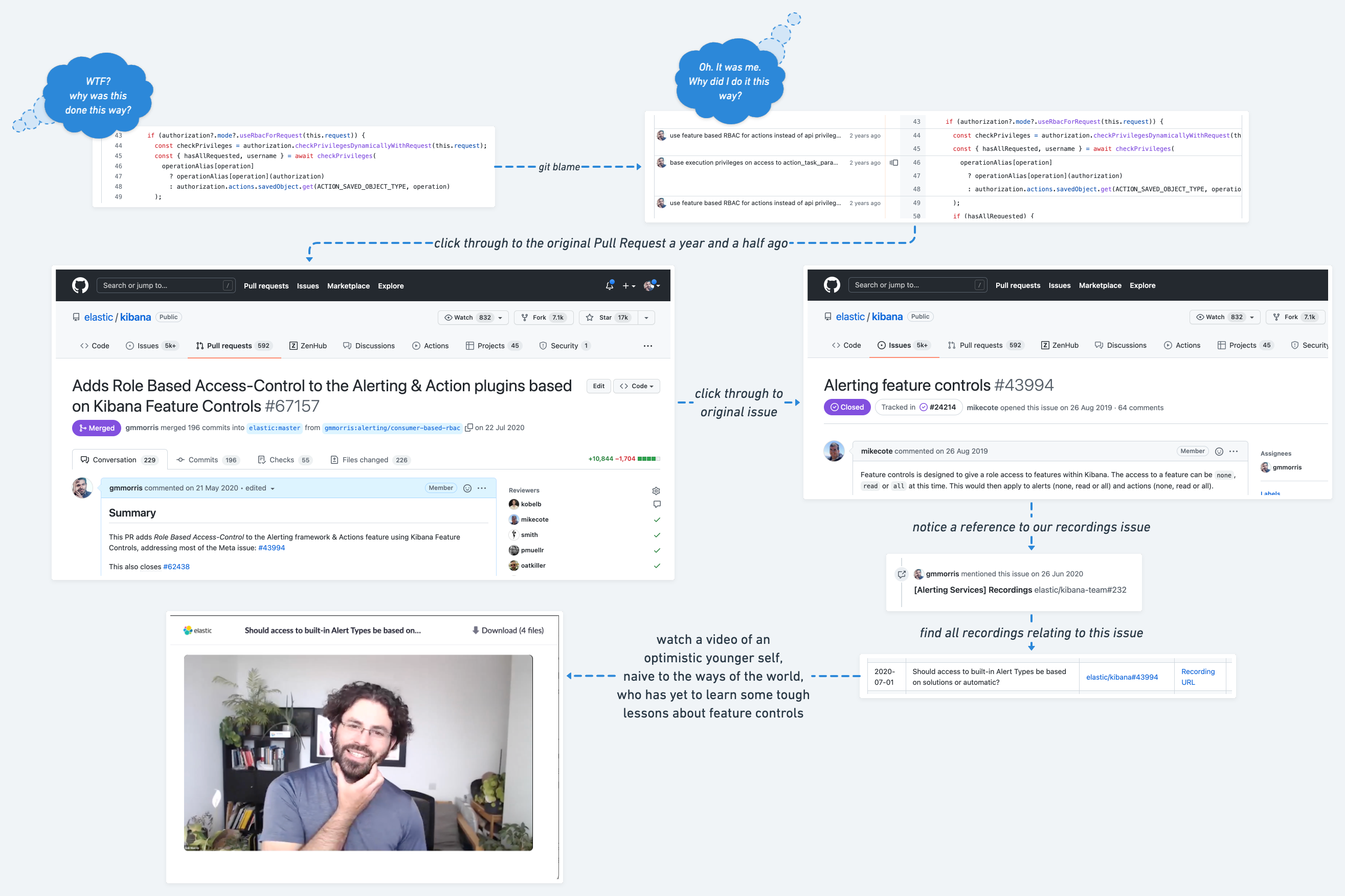

A bug report comes in, we reproduce the issue locally and locate the offending code. Reviewing the code, a sigh escapes our lips, followed by a semi-rhetorical question: “Why the f**k did we do it this way?”

We pull up our terminal and type git blame just to see our own name staring back at us.

“Oh… Why the f**k did I do it this way?”

The working agreements example was a fairly straightforward one - hold a meeting, record it, and link to the recording next to the recording notes. Hardly groundbreaking.

It’s with the next example though where the chain of archived context, really shines, and this is where my true aha-moment took place.

The git blame command, which tells us who the developer was that committed the offending code, also gives us the pull request that merged it.

The nice thing about how services like Github work, is that this pull request also links us with the issue where the user story and requirements were discussed.

This is already a great place to be as the issue includes lots of valuable context, thanks to the prioritisation of asynchronous communication. But what if, in addition to the issue, we also have links to recordings of all the meetings where we discussed the work? What if, thanks to the unusual ease with which we were able to document and access this context, we can now spend an hour rewatching those meetings (at x2 playback speed, obviously), regaining all the context we had two years ago?

How much easier will it be for us to address this bug now that we know why it was done this way?

Now, imagine if these meetings took place two years before you joined the company? These recordings are no longer reminders, but rather discoverable and focused onboarding material that your team put in place long before they knew you’d need it.

You’re now better prepared to fix a legacy bug than I have ever been on any co-located team these past 20 years as an engineer. Now that’s an aha-moment!

A Tip for Those Who Develop in the Open

While only a portion of Elastic’s software is technically open source, the vast majority of it is developed in the open. This means that, for the most part, our code, issues, pull requests, and documentation, are visible to all on our github account.

As an engineer, I find developing in the open to be a wonderful and humbling experience, but at times it also feels exposed and observed. As a result, not all communication can, or should, take place in the open, and at times we might want to link to a recording that we would prefer to keep internal.

We could link to a password-protected recording, but we love our community and believe this provides them with a poor experience when contributing to our software. Luckily, Github provides a very good facility for this, as it allows us to refer to issues the other way around.

In our private repositories, we can keep issues that reference issues in our public repositories, and we can provide links to our recording in those private issues. When you view a public issue, this reference will appear on the issue, but is only visible to users who also have access to the private issue - meaning they are other Elasticians, with whom we wish to share this context.

Recording Intent the Easy Way

RFCs, ADRs, and other means of documenting decisions are all about recording the original intent in a discoverable manner. When your culture instinctively records decisions in an asynchronous means of communication, it becomes easier to maintain an archive of these decisions.

What I have discovered over the past few years, is that working remotely makes this sort of thing easier, but working distributed makes these things intuitive and as a result - the easiest.

An interesting nuance I have found is that truly distributed teams, where their members are spread out across multiple time zones, find this far easier than teams that are in the same timezone. We’ll discuss this in the third part of this essay, On Managing Distributed Teams.

- To be clear, this isn't an engineers problem, as I've seen the exact same behaviour exhibitted by product managers, business development people and more. I find humans struggle to think about their future needs once their immediate need has been addressed.