Two years ago our entire industry, and to a certain extent most office-based industries, was thrown into a new remote-first reality by a global pandemic. This was particularly interesting for me as, unlike most of my friends and my family who found themselves forced into an unfamiliar work environment, I did not. For me, this was already familiar ground as six months earlier in late 2019, I had intentionally chosen to go remote by joining Elastic, which has operated as a remote-first team since its inception.

My interest in remote work began as a team lead at Unruly, where my team and I had been trying to introduce remote work and were finding it hard. To be more accurate, we were failing miserably at it. Following years as practitioners of Extreme Programming, utilising pair programming, agile boards, and co-located osmotic communication, we couldn’t figure out how to balance remote work with the heavy reliance we had developed on in-person collaboration.

With an interest in addressing this gap in my competency, I decided to join Elastic, as I wanted to learn how an engineering team as large as theirs was able to scale and operate in a remote-first fashion.

What I’ve learned from my time at Elastic has been that remote ≠ distributed, and that doing so well requires you to learn to collaborate asynchronously. This is hard and, discussing this topic with friends and colleagues, I have come to recognise as not well understood. This is, I believe, why many of them have struggled to make their teams’s shift to remote a success.

Remote ≠ Distributed

We tend to talk about engineers who work on Distributed Systems with a certain degree of reverence. Mostly, this is because distributed systems tend to make problems harder to solve due to the high cost of coordination throughout the constituent parts of the system.

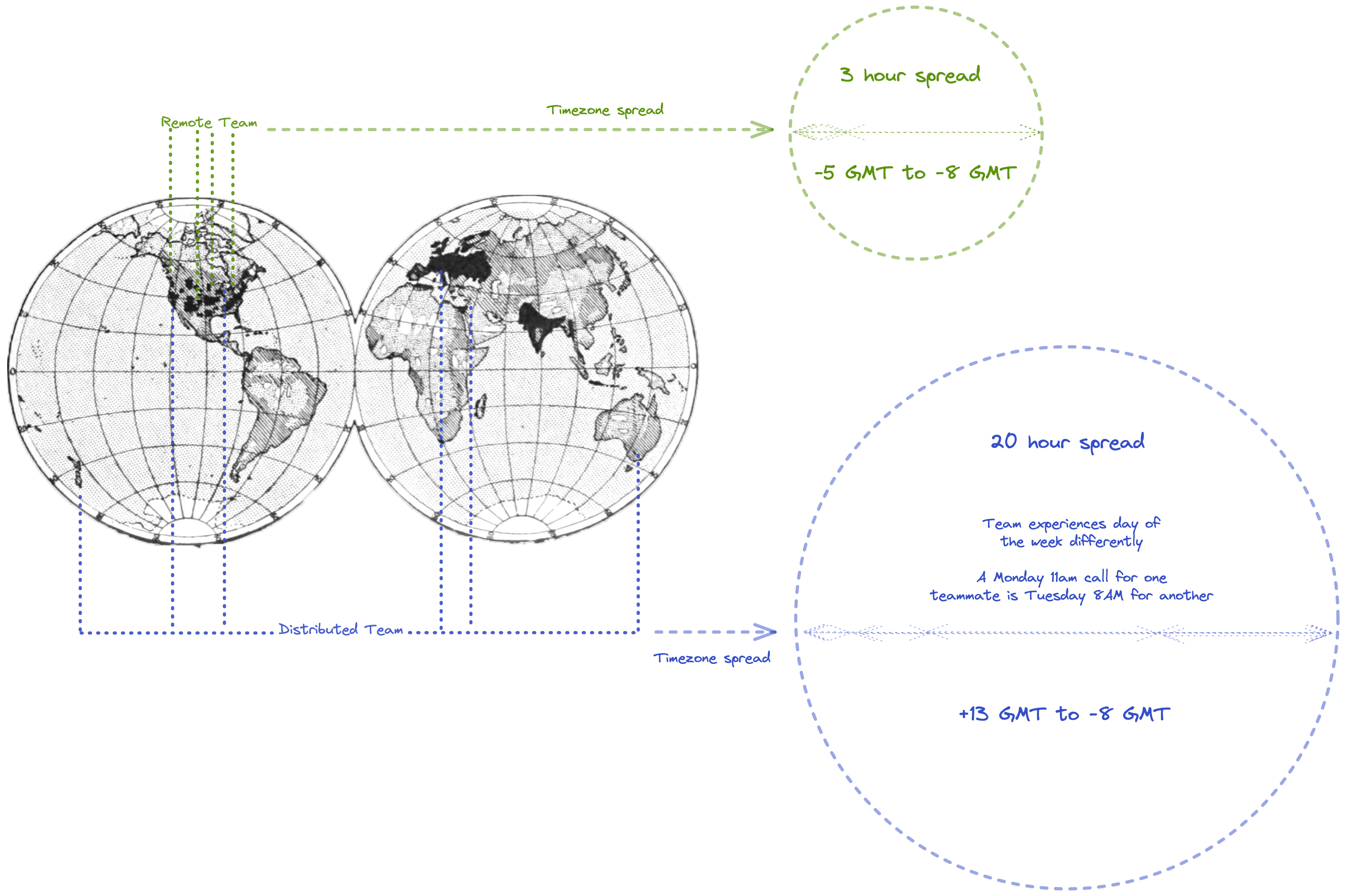

This is as true for human systems as it is for software systems, which is why remote collaboration, a form of a distributed human system, is harder than co-located collaboartion; and as we have learned over the years, software engineering is an exercise in human collaboration more than anything else. It’s a team effort, and if we were to compare those challenges that make co-located collaboration hard with those afflicting remote and distributed team, we would find that the gap between remote and distributed is as wide as the one between co-located and remote.

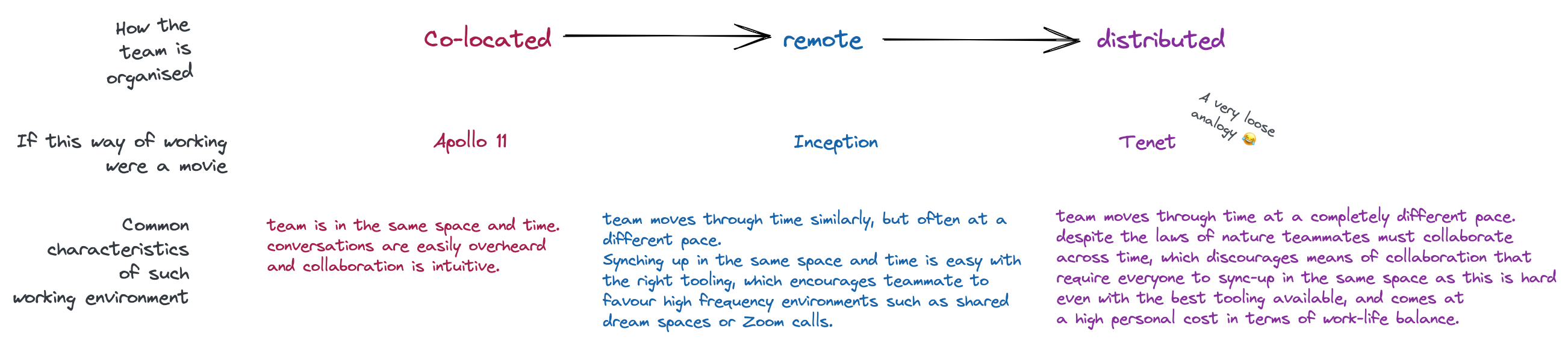

A nice simile for this gap, which might be less helpful if you’re less of a nerd than I am, is that a co-located team is to a remote team as the team on Apollo 11 is to the team in Inception; but a distributed team is more like the team in Tenet.

I’m exaggerating, obviously, as distributed teams don’t have to, spoiler-alert, collaborate across the plains of an inverted time dimension. That said, unlike most of the remote teams formed by the digital transformation of the global pandemic, they do have to collaborate in an environment where their teammates are out-of-sync with each other. This is where an Intentionally Asynchronous culture where asynchronous communication is not only encouraged, but enforced, is demonstrably impactful.

Being globally distributed means that any role that can be distributed, should be, as it enables the organisation to maximise its diversity and its ability to hire the best person for the job, no matter their location. Elastic, is globally distributed by design and intention. This means that however we collaborate, it has to enable every role in the company to operate no matter the teammate’s chosen timezone. Ideally not an inverted time dimension, but for the right candidate, we’d make it work 😉.

Distributed by Design

I mentioned above that the ideas of a globally distributed team and being intentionally asynchronous aren’t well understood, and I’d like to address that by sharing what I have learned over the past two and a half years of work at Elastic, in a three-part essay:

Part I: Intentionally Asynchronous covers some practical practices that Elastic has adopted to successfully scale as a distributed company.

Part II: A Chain of Archived Context explores a couple of real-world examples where, in my opinion, asynchronous communication improves on in-person collaboration by empowering teams to archive their communications and link these archives to the source of truth, which enables teams to retain context across generations.

Part III: Managing Distributed Teams covers some of the things I’ve learned from managing teams in a distributed setting. These are very subjective and anecdotal, but I believe they are also worth sharing.

- Though they are better placed to do so, thanks to their archived communications, and we'll get to that in Part II: A Chain of Archived Context.