When the pandemic hit engineering teams in 2020, most of them scrambled to migrate their existing working processes to a remote friendly setting. I dislike the term remote friendly, as it doesn’t tell me anything about how suitable the process is for remote work, and is usually more of a frenemy, than actually suited to the realities of remote work.

This is why many of my former colleagues, realising mid-way into 2020 that this new reality was not going to come to an end any time soon, reached out to me for advice. How does Elasic make this work?, they asked.

Their companies, who seemed to have realised the same, began distributing articles filled with banal statements such as “Communication is key” or “Stick to your work schedule”, but no one explained how this is achieved. The better articles would take a step in the right direction, by advising people to switch to asynchronous communication and to create a culture of unblockable work, but rarely did they explain how.

This post is part of the Distributed by Design essay, which begins with Remote isn’t Distributed, describing what I learned over two and a half years as an individual contributer and manager on a distributed team at Elastic.

Part I: Intentionally Asynchronous

Elastic practices asynchronous communication as much as is feasible, and are intentional about enforcing asynchronous practices even where they are seemingly less necessery. I’ll be honest and admit that I have noticed that, even within Elastic, the degree to which different teams succeed at applying these practices tends to vary widely, but let us begin with the basics: How does Elastic set a baseline of async communication?

As a fledgling remote-first company Elastic leaned heavily on a communication style that is best described as loose distributed consensus, interacting primarily by the means that were common place in the open-source community at the time, such as email, and IRC. Given the open-source background of the individuals involved this choice not only made sense but was easy to pass on to newcomers. It didn’t take long for the company to learn that this sort of informal assimilation of communication norms does not scale, and fearing their culture might be at risk, formalised this culture by various means.

I’ll focus on two of these formal means, the Source Code and the Communications Charter, though it is worth noting that there are other formalised means in place to address the variety of needs across the organisation. The informal practices born out of async work are just as interesting, in my opinion, but we will touch of those in parts II and III of this essay.

The Source Code

When I began researching Elastic, as I do all potential employers, I stumbled across their Source Code. The Source Code doesn’t refer to the actual code that powers their products, but rather a set of ideas that Elastic says “are some of the things that make Elastic, Elastic”. At the time, I thought this was just marketing material but have since come to learn that I was wrong and that the Source Code is an ethos that many, if not most, Elasticians hold dear and truly believe in.

Quoting from Elastic’s own blog post about their distributed culture:

To promote these ideas we developed the Elastic Source Code as a kind of ethos, a guiding light, and an extension of our distributed mindset. Each component of the Source Code is focused on what it means to work from home, that each environment and each life is different, and that Elasticians who are free to come as they are and who are able to find the space and time to do their best work, will always bring 100%.

I know, I’m verging on the edge of being labeled a marketing puff piece myself here, but my experience with my managers, and executive leadership in the company, has shown that following the Source Code really is a priority for everyone involved.

The Source Code covers far more than just the distributed nature of how we work, and so I’ll call out three specific ones: Home, Dinner, 01.02, /FORMAT, and As YOU, Are.

Home, Dinner

It’s no coincidence that Home, Dinner is the first idea in the Source Code.

To quote:

There is no such thing as work-life balance. We are successful if we find balance in life. Elastic empowers you with the flexibility to do so. Be home for dinner, go running midday, care for a sick child, or visit a parent. Finding balance means being more innovative and efficient at work. Which makes for a better Elastic.

It’s a reminder to everyone involved that we work to live, not the other way around. It’s a reminder that it’s not just ok to prioritise family time but rather it’s the expectation.

The wonderful thing about Home, Dinner is that, unlike in a co-located company, or a remote-but-same-timezone company, dinner time is a completely different time depending on what timezone you live in. This means that every one of your teammates is expected to be away for their family’s dinner time at whatever time works for their family. You can’t just expect a colleague to attend your meeting because it’s 10AM your time… it might be dinner time for them, as they live on the opposite side of the planet. And that’s ok.

This culture, naturally, extends itself beyond dinner time. You want to exercise, go to your kid’s school activity, or attend your best friend’s Rocky Horror Picture Show afternoon bash? That’s fine.

This has some fascinating side effects.

Firstly, strict work hours are nonexistent. We trust you to fit the work time around your life as needed, and accept that it is unreasonable to expect you to be available at the precise time we happen to set the meeting. This is hard.

The Communication Charter helps us lay out how to achieve this, but I repeat: This is hard.

Secondly, managers have to recalibrate how they assess individual productivity and track work. On the one hand, it’s harder to tell when members of your team are working, and need to find better ways to track progress and productivity. On the other, decades of work in co-located teams have trained me to perceiving work hours as a proxy for overwork, and I can no longer rely on that. I have to trust my teammates when they work at hours that might seem unusual to me, and avoid the assumption that they are overworking.

These side effects have pushed me further outside of my comfort zone as a manager, and we’ll cover that in Part III: On Managing Distributed Teams.

Format As You Are

The 01.02, /FORMAT and As YOU, Are ideas tackle two related, but distinct, aspects of being a globally distributed team. None of the advice I can give you with regards to asynchronous communication will ever work if you can’t cultivate an empathetic culture.

01.02, /FORMAT states:

Our products are distributed by design, our company is distributed by intention. With many languages, perspectives, and cultures, it’s easy to lose something in translation. Over email and chat, doubly so. Until we get a perpetual empathy machine, don’t assume malice. A distributed Elastic makes for a diverse Elastic, which makes for a better Elastic.

And As YOU, Are:

We all come in different shapes with different interests and skills. We all have an accent. Celebrate it. Just come as you are. No need to invest neurons trying to fit an arbitrary mold. We’d rather you put them to work shaping Elastic.

Our communication skills suck and our tools tend to amplify that fact. This is one of the many reasons why your experience of remote work over the past two years might have felt alienating or isolating. Our technology has trained us to focus communication on our own needs with little consideration for how the person on the other side might experience that communication.

When I hit “send ✉️” I can’t know what frame of mind the person on the other side is in, nor what device they are on.

Perhaps that rushed email I sent a colleague has failed to provide sufficient context, or was inappropriately long. Perhaps the mix of font colours and meme gifs don’t render appropriately on their mobile device or their screen reader?

This is true in any environment, but in a globally distributed team, spanning 18 timezones, and over 40 countries, there is more room for misunderstanding or miscommunication than I have ever experienced.

Developing sufficient empathy for your colleagues that you see 01.02 as Schrödinger’s date - simultaneously the same and different dates, depending on your cultural point of view. And As YOU, Are is not just a tribute to Kurt Cobain, but also a reminder that we are a diverse group of individuals, with very different life experiences, all of which effect our communication. Accents, idioms, figures of speech - these are both a wonderful part of our diversity and a potential pitfall.

Warning teammates of this pitfall is only one part though, as the fear of falling into the pit could be so debilitating that it keeps people from communicating important information out of fear of misunderstandings.

This is why we ask our colleagues to always assume misunderstanding, and not malice.

I’ve lost count of the number of times I’ve heard individuals at Elastic quote that part of the Source Code. I’ve heard it from our CEO, execs, managers, and engineers. We are constantly reminding each other, and ourselves, of this tenet.

I’ll also mention that, when it comes to my own team, I have taken a leaf out of Steve Hayes’s book and have repeatedly talked with them about fundamental attribution error, and how necessary it is to keep it in mind at every turn.

The Communications Charter

The Source Code is a little abstract, I know, as it gives you a bit of an insight into how the leadership of Elastic set a baseline, but it still doesn’t give you practical guidance. This is where the Communications Charter comes in.

The Communications Charter is a document that outlines the expectations that Elasticians have of each other with regards to how we use the variety of communication tools at our disposal. The charter is specific to Elastic’s choice of tooling and organisational structure, but in this section, I have attempted to boil it down to a set of best practices that are universally applicable.

If you choose to create your own Communications Charter I would recommend following this example and making it specific to your team’s choice of tooling and culture. Crafting this document as specific as possible makes it more applicable and encourages individuals and teams to enforce these practices.

Asynchronicity and Decision Making

Before we talk about the tooling itself, and discuss the qualities inherent to asynchronicity, lets make sure we’re clear on why it matters.

Being intentionally asynchronous means that teammates are expected to consume information at some point after it is sent and that, as long as it is consumed in a timely manner, it is unreasonable to expect an immediate response. This forces teams to rethink how they achieve certain tasks, especially those typically accomplished via in-person meetings. Often these tasks are just as effectively and inclusively accomplished via asynchronous means as they were synchronously, and doing so frees them from the need to sync up on a regular basis.

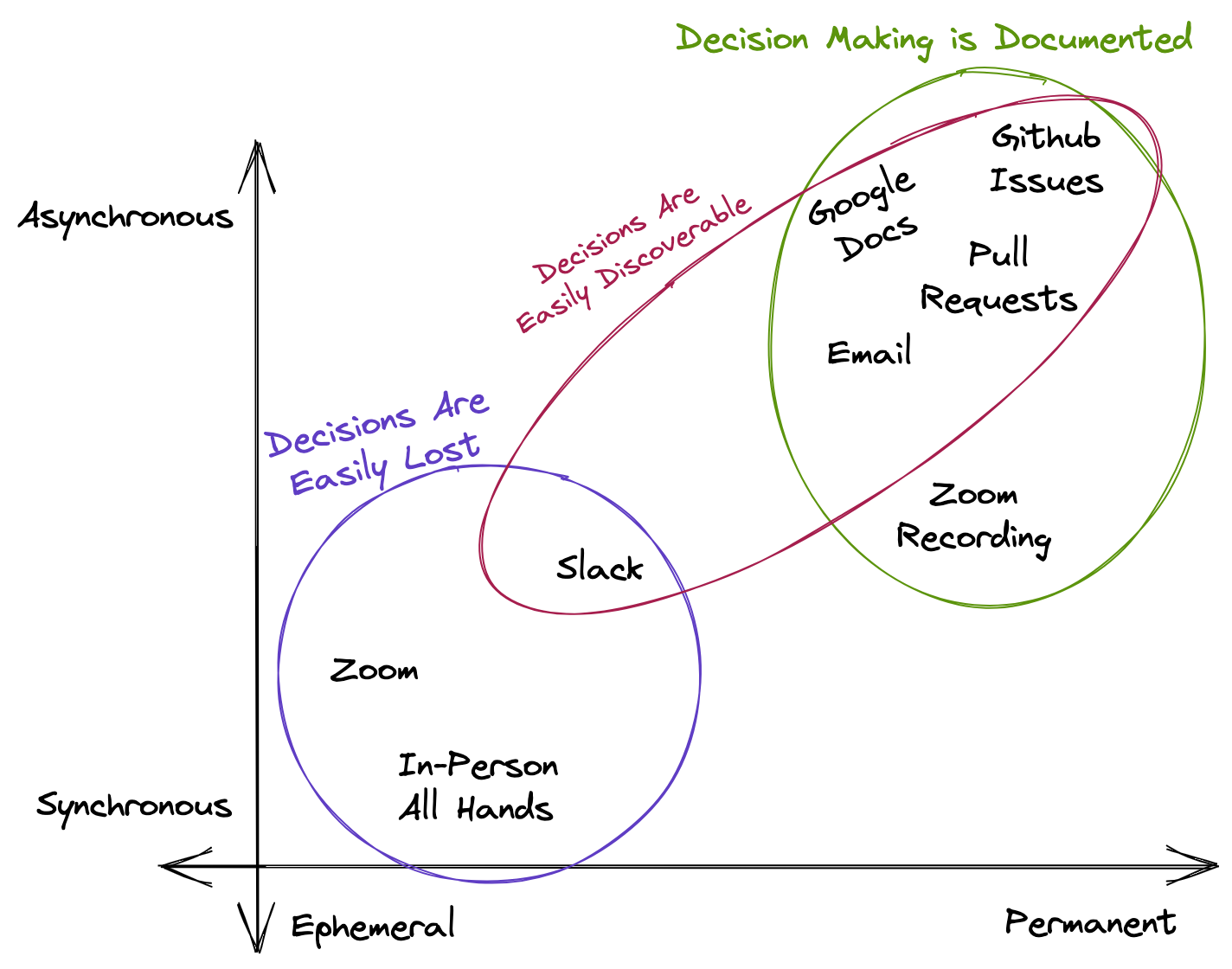

To achieve this, the charter sets explicit expectations with regard to decision-making. The general rule of thumb is this: A decision hasn’t been made until it has been documented in a permanent asynchronous medium.

Synchronous collaboration is valuable, and I’ll touch on that in a moment, but once your meaningful synchronous interaction has borne fruit, summarize it over the appropriate asynchronous medium and disseminate it to the relevant audience.

Ephemeral vs. Permanent

As mentioned before, being intentionally asynchronous is hard, so let us be explicit about what we mean by asynchronous.

I think it’s fairly obvious why a face-to-face conversation, or it’s remote equivalents such as Zoom or MS Teams, are synchronous. But what about instant message tools like Slack or Google Chat?

Additionally, from the opposite end, I think it’s fairly obvious that Email is asynchronous, but does that mean I have to go back to the days of Email Hell? What is this, 1998 again?

Instant Real-Time communication

The way many people use Slack, they assume that the person on the other side will be instantly available, and responsive. This expectation doesn’t lend itself well to a distributed team, where channels can get busy, information is easily sharded and lost. In Elastic we do use Slack intensively, but we consider its existence temporary and unreliable, and as such the charter considers these tools both synchronous and ephemeral.

When using Slack we recognise that a portion of the team is likely to miss any detailed conversation taking place about technical implementation, prioritisation, or competitive strategy. Expecting our teammates to catch up when they wake up is neither scalable nor inclusive.

Don’t get me wrong, Slack is probably the busiest channel of communication in Elastic, but you’ll find Github Issues, which we consider asynchronous and permanent, give it a run for its money.

That said, when it comes to instant messaging, I feel like Slack have done a good job of recognising their target audience, and have built a tool that comes well equipped with the features needed for healthy asynchronous collaboration. In fact, many of the best practices in our charter are covered by Slack’s own ettiquete tips.

That said, there are some best practices that they have missed and I feel are worth calling out, as they relate less to etiquette and more to building an asynchornous culture.

Don’t make decisions on Slack, and if you must, document them elsewhere. I know, I’m repeating myself, but this is probably the most important takeaway from this entire blog post. In fact, if this blog post were a tweet, it would just be this: Try not to make decisions on Slack or Zoom, and if you must, always document them in Email, Github Issues, or Google Docs afterward.

Treat Slack as a walled garden that could be lost tomorrow Though this is true of Github as well, we treat Slack as completely ephemeral and should always treat the data inside of it as potentially gone tomorrow. Any and all knowledge that must be retained should live in Email, Github Issues, and Google Docs.

Source Control as an Ecosystem for Communication

Elastic uses Github intensively, all across the organisation, to track, execute, and maintain a record of work.

We have repositories dedicated to our technical products, but teams also maintain dedicated repositories for collabroation. Issues are filed for onboarding, to discuss working practices and agreements, or documenting discussions that have taken place. As a result teams are able to leverage the same tooling used to track technical work, collaborate on code, and maintain a backlog of work, in order to track, collaborate on, and archive other aspects of our team dynamics.

Teammates submit PRs with improvements to the content in their team repositories, in the same way they contribute improvements to code. Whether they’re proposing an improvement to a working agreement, an onboarding issue, or internal documentation, other teammates are able asynchornously review the suggestion, collaborate and iterate on it, and merge the resulting improvement. Teammates can file issues with questions, allowing others to weigh in, add context, and then close the issue when the question has been answered. This provides the team with a record of past learnings that would have otherwise been lost to the ether had they been asked in Slack or over Zoom.

As the default asynchronous communication tool throughout our industry, the practices we’ve developed around Email are, unsurprisingly, universal. Most of the expectations set out in the charter are echoed by 99% of search results on the topic, but I’d like to call out a handful of particularly valuable practices I’ve picked up since joining Elastic.

Email threading is broken, doesn’t scale, and it blows my mind that we still haven’t solved that in 2022. For this reason, subject lines should be unique, clearly identifiable, and must communicate intent well. If you wish to fork a thread for the benefit of a new audience (especially if this is aimed at a subset of the original audience), explicitly change the subject line for the benefit of both yourself and any teammates that now find themselves in two separate threads.

Add TTLs to Emails to avoid unbounded requests. By adding a TTL to an email subject line, such as [TTL Fri, Dec 3rd], I communicate to my colleagues that they have a specific timeframe by which to weigh in, after which I will consider their lack of feedback implicit approval of a proposed course of action. This enables your audience to more easily prioritise their work, and communicates to other participants when they might expect any follow-up actions to take place.

Use TL/DRs and explicit audiences to reduce noise. By adding a TL/DR at the start, or clarifying who the intended audience is, you can dial down the noise by narrowing down the number of people who have to consider the Email relevant to them. Furthermore, when a specific audience is clear, we try to use a dedicated group, as groups act not only as an audience filter but also as an archive for all communications relating to this group or domain.

The sun rises and sets differently for each of us so don’t use terms like end of day, seeing as your day might have ended before your colleagues has even begun.

In early 2020 I spent a month in New Zealand, working from my partner’s family home. I would often attend an early morning meetings, while my teammates were experiencing that very same moment as a late afternoon meeting taking place in my yesterday 🤯. It was at that moment that I realised how easily misused the term End of Day can be.

Always use concrete dates, and never forget about 01.02, /FORMAT.

Of all these practices, the one most universally applicable is likely Email. Every company I have ever worked at relied heavily on Email, and these skills are most likely to remain applicable throughout your career, whether you’re working in a distributed team or not.

Synchronocity and Collaboration

I’m a big believer in the importance of small bursts of collaboration, and there’s little doubt in my mind that these are more common in synchronous forms of communication. But if I’m being honest, I doubt the percentage of in-person meetings I’ve attended in my career that would qualify as a burst of collaboration exceeds a tiny fraction of a percentage point.

Imagine an ideal workplace where the only synchronous interactions are those that facilitate these bursts of collaboration (and yes, I include team bonding in that). Now, set that ideal as your goal and constantly iterate to achieve that.

I’m not going to pretend that Elastic has achieved that ideal, but this ideal has been a north star for my teams and I. We aim to make our interactions as asynchronous as possible, and strive to make every synchronous meeting a burst of collaboration. When we feel like a meeting has failed to provide us with that quality, we reconsinder whether it is actually neccessery.

Zoom, the Frigidaire of video calling

Pretty much all synchronous collaboration in my team takes place over Zoom.

This is a necessity given our distributed nature, which has us split across no less than 6 countries (12 if we count states 😉) and spans a time difference of up to 10 hours.

Every once in a while, teammates might meet up in-person while traveling, and before the pandemic we would hold regular in-person all-hands, but you can’t hold off on collaboration in anticipation of the next in-person opportunity. We learned early on that any collaboration neccessery for the team to function well has to be possible by remote means. This allows us to savour those precious moment of in-person collaboration for things that are harder to do over video, bonding over shared experiences such as sight-seeing or sharing a meal.

When it comes to best practices for Zoom, you’ll find a lot of overlap with Slack, but there are some unique points worth considering:

When you make decisions on Zoom, as we all know you will, document them elsewhere. I won’t labour this point any further. Always document these decisions somewhere asynchronous and non-ephemeral.

Record meetings whenever possible and document the recording. This is one of the key practices I’ve taken away from my time at Elastic, and hope to carry with me for the rest of my career.

While my last company, Unruly, was by far the most collaborative environment I had ever had the privilege of working in, it was terrible at retaining historical knowledge and context.

In Elastic we record most of our meetings, whether they are recurring meetings such as planning sessions, or ad-hoc “I’d like to pick your brain”-type meetings. I’ll expand on an aha-moment I had regarding this practice when we discuss the chain of archived context, in part II.

If this zoom call could have been an Email, make it so next time. If you’ve ever attended a Zoom call with dozens of attendees you’ll know what I’m talking about. Most likely, when attending a meeting like this, not everyone on the call was necessary nor have they gained value from attending the call synchronously. Whenever I attend a meeting like this I ask myself whether this could have been an Email, or a session best attended by a handful of people and distributed later as a recording.

I mention this point as, for many teams (including in Elastic), it is this sort of meeting that makes it so incredibly hard to become truly asynchronous and distributed. The synchronous all-hands or cross-team sync-up call, often with required attendance, is now an anchor that has to be dropped somewhere in the time-space continuum. This anchor is best avoided as much as possible.

Learn more about Distributed by Design

Part I has covered the practicalities of Elastic’s formal baseline for asynchronous collaboration.

I invite you to learn more through Part II: A chain of archived context and Part III: On Managing Distributed Teams, where I cover some less formal practices, and anecdotal lessons that I have learned over the past two years of managing distributed teams.

- I've found that the variation usually correlated with how wide the timezone spread is within the team and we'll touch on this variation in Part III: On Managing Distributed Teams.

- They are referring to the ideas of being intentionally distirbuted, prioritising people's freedom to prioritise life over work, and so forth.

- A recent Twitter thread has me thinking there's a potential pitfall here too, but I feel like the Source Code does a good job providing the nuance needed to reduce the likelihood of bad actors taking advantage of it.

- To be honest, I'd be more than happy if our entire backlog of Github Issues were nuked tomorrow, forcing teams to ask themselves _"what is the next most-valuable deliverable for my customers?"_, but that's a blog post for another day.

- This is no longer true once a question asked on Slack or Zoom is appropriately documented. Many questions are discussed and resolved over Zoom, for example, but as long as we document this question in a discoverable manner by linking it to the appropriate context, such as a Github Issue, then we can still benefit from async communication. We will see this in action in Part II: A Chain of Archived Context.