In 2022 I co-founded a NatureTech company called NatureBound. I haven’t written about this yet, and frankly, I wasn’t sure when the right moment would come. But I’ve been thinking a lot about product theses and antitheses, and it felt like a good lens through which to process what we tried to build - and why it mattered, even though we didn’t succeed.

That year, I left big tech to focus on climate change and nature. It was a deliberate shift, one I’d been contemplating for years as I watched the compounding effects of ecosystem collapse play out in real-time. I was suffering from pretty bad climate doomism at the time, and it weighed on me that while I sat there, optimising ad delivery systems, it seemed like no one was doing much to prevent the planet from dying. That wasn’t true, of course, plenty of people were working on these problems, but I couldnt see that from inside the tech bubble.

What began as an idea, crystallised into a decision when I realised that there’s no point having career ambition if there’s no planet left to sustain it.

NatureBound and the People Behind It

I co-founded NatureBound with two remarkable people who brought perspectives I could never have developed on my own.

Marianna was an entrepreneur who spent years in the food space, navigating the messy intersection of sustainability, supply chains, and consumer behaviour. She understood the business realities of food production in ways I never could from my engineering background - the razor-thin margins, the complexity of global supply chains, the challenge of making “doing the right thing” economically viable.

Iqbal was a young and energised PHD Ecologist with a deep passion for biodiversity monitoring. His focus on bats and their critical role in agriculture opened my eyes to the invisible interdependencies that keep our food systems functioning. He’s now teaching at the University of Saskatchewan, training the next generation of ecologists who’ll inherit the challenge of protecting what’s left.

The three of us came to the problem from different angles, but we shared a common conviction: agriculture sits at the nexus of the climate and biodiversity crises, and if we could help make farming more compatible with nature, we could create meaningful change at scale.

We each had personal connections to this space. I grew up in an agricultural area - my first job was collecting eggs in the shadow of what was then the biggest chicken coop in the Middle East. Iqbal’s research into bats revealed how these often-overlooked creatures provide billions of dollars worth of pest control services to farmers worldwide. And Marianna, a true foodie who had co-founded a children’s healthy snack company in the past, brought years of experience working to make food systems more sustainable and equitable.

We Shut Down in 2024

Enough time has passed since NatureBound folded in 2024 that I feel ready to document what we tried to build. We ran the experiment, we learned an enormous amount, and ultimately we couldn’t make it work within the constraints we faced. I still believe in the idea and I want to capture what we were building, both for my own clarity and in the hope that someone (maybe even me, in a different context) will pick up this thread in the future.

Startups fail for a thousand reasons, most of them mundane. Market timing, funding dynamics, team capacity and capabilities, regulatory headwinds. We hit some combination of all of these. But the underlying problem we identified? That hasn’t gone anywhere. If anything, it’s gotten more acute.

So this is a product thesis for a company that no longer exists, but for a problem that very much does.

Why I’m Writing This Now

There’s another reason I’m documenting this now, and it’s worth being transparent about: I’m joining NatureMetrics, to lead the engineering team working on their Nature Intelligence platform. I’ve watched NatureMetrics, a company I’ve always thought of as “the eDNA company”, evolve to offer a much more holistic offering, which suggests they may be moving in the same direction we were at NatureBound - something I can’t wait to explore. I wanted to get all of this context down on paper before I begin my new role, for two specific reasons.

First, I don’t know anything proprietary about NatureMetrics yet. Once I’m inside, these thoughts would become impossible to publish - there would always be the question of whether I’m drawing on internal knowledge or strategy. Writing this now preserves the independence of these observations.

Second, and perhaps more importantly, I’m sure I’m wrong about many of these things. The ideas in this post represent my current understanding, shaped by the NatureBound experience and dozens of customer conversations, but they’re still just hypotheses. It will be fascinating to look back in a year or two and see how much I got wrong, and how much companies like NatureMetrics - who’ve been in this space far longer than I have - got right. This is my stake in the ground, my “before” snapshot.

So take everything that follows with appropriate skepticism. This is what I believed the product opportunity looked like based on what we learned. Reality, as always, is more nuanced.

The Problem: Biodiversity Loss as an Agricultural Crisis

The loss of biodiversity represents an existential threat to human civilization, and agriculture is both a primary driver of that loss and one of its most vulnerable victims. Modern farming has created a negative feedback loop: intensive practices degrade ecosystems, which reduces the natural services those ecosystems provide to farms (pollination, pest control, soil health - to name a few), which drives farmers to rely even more heavily on costly chemical inputs, which further degrades ecosystems.

Breaking this cycle requires visibility into what’s actually happening at the ecosystem level - and that’s where things get complex. Not just complicated with many moving parts, but genuinely complex: ecosystems are adaptive systems where cause and effect aren’t always linear, where interventions can have unexpected consequences, and where context matters enormously.

During our customer discovery process, we found that the people we spoke to largely understood this. Corporate sustainability officers, food buyers, agronomists - they cared about the role of nature in their businesses and they could see it was impacting them. The challenge wasn’t awareness. The refrain we kept hearing, from different angles and in different words, was: “We get it, but we don’t know what to do about it.” And when they did invest in collecting data - spending tens of thousands of pounds on eDNA surveys, bioacoustic monitoring, remote sensing - they still couldn’t translate what they got back into action.

This broke down into two interrelated problems:

Data fragmentation. The NatureTech space is still in its early stages, and the people building these technologies come from wildly different backgrounds - foresters, biochemists, geospatial analysts, climatologists, ecologists, soil scientists. Each discipline has its own data formats, methodologies, and vocabulary. You might have eDNA surveys revealing which species are present, remote sensing data showing land cover changes, soil chemistry analysis, pesticide and fertiliser application logs, crop yield data - all of which influence and are influenced by biodiversity. But none of them tells you what you actually need to know in isolation. This fragmentation makes it nearly impossible to interlace data sources into a coherent picture of what’s happening ecologically.

The “so what?” gap. Even when data was collected, it sat in reports that told people species were present and habitats existed, but not what to actually do about it. Consultants and technology providers promised insights that would transform operations and de-risk supply chains. Companies would invest in data collection and then… nothing actionable came back. The insights that actually matter - Is this population of natural predators sufficient to control pests? Are we seeing signs of ecosystem degradation that will impact yields in three years? Which interventions would have the highest ROI for both nature and farm economics? - these require interlacing multiple data sources in sophisticated ways and then translating that into actionable recommendations.

Together, these two problems left everyone we spoke to stuck. Corporate buyers couldn’t assess the supply chain risks they knew were coming - and even if they knew to engage the domain experts who could help, those agronomists and ecologists faced their own impossible choice: either try to purchase, produce, integrate, and analyse all these data sources themselves - which requires both budgets they don’t have and expertise across multiple scientific disciplines they can’t reasonably possess - or give incomplete advice based on partial information. For most, the former is simply impossible. So they’re stuck making recommendations without the full picture, unable to help farmers optimise for both economic and ecological outcomes. Or worse, they spend the money on data collection only to discover they still don’t know what to recommend.

Product Thesis

A product thesis is essentially a bet - a clear statement of what you believe is true about a problem and how you think a product can solve it. It’s your hypothesis about the world that, if correct, makes your product valuable and viable. Think of it as the “if this, then that” at the heart of a startup: if corporations need biodiversity reporting and farmers need actionable insights, then a platform connecting these needs creates value for everyone.

Our product theisis evovled a lot over two years, but looking back, here’s how I’d frame our underlying thesis:

Corporations with agricultural supply chains face increasing pressure to report on their nature-related dependencies and impacts, while simultaneously worrying about the long-term sustainability of their supply chains. They need visibility into biodiversity health within their sourcing regions, but lack the tools to collect, integrate, and act on that information efficiently.

We can create a positive feedback loop that aligns corporate reporting requirements with on-the-ground ecological improvement.

The mechanism works like this:

-

Corporates fund data collection because they need it for mandatory nature-related reporting (TNFD, CSRD, etc.) and supply chain risk assessment.

-

Our platform makes it easy to determine which data to collect and where, using an intelligent recommendation engine that accounts for crop types, regional ecology, existing data availability, and reporting requirements.

-

We interlace diverse data sources - remote sensing, eDNA, field observations, farm management data - into a unified analytical layer that provides a holistic view of biodiversity health.

-

We map this to standardised impact and dependency metrics that corporates can use for their reporting obligations, showing both current state and trends over time.

-

We generate actionable insights for farmers and agronomists operating within those supply chains, enabling them to make decisions that improve ecological outcomes while also reducing input costs or improving yields.

-

Demonstrable improvements flow back into the next reporting cycle, creating a virtuous loop where corporate investment in data collection leads to better on-the-ground practices, which leads to better metrics, which justifies continued investment.

The key insight, as I see it now, was that though the people who need the data (the corporate sustainability team) and the people who can act on it (the agronomists and farmers) are not the same, their interests and incentives can be aligned if you build the right connective tissue.

User Personas

User personas are fictional but representative characters that embody the needs, goals, and pain points of your target users. They help you think concretely about who you’re building for and keep you honest about whether your solution actually solves real problems for real people.

Personas paired with scenarios are powerful alignment tools. It’s easier for teams of engineers, product managers, and commercial stakeholders to align on a compelling story about how someone uses the product than it is to align on a shopping list of features. A good scenario makes trade-offs clearer and keeps everyone focused on solving real problems rather than building what’s technically interesting.

Looking back, here are the people I believe we were trying to help. For each persona, I’ve included a north star scenario: an aspirational vision of how the platform would ideally work for them.

Sarah the Boardroom Advocate (Corporate Sustainability Officer)

Sarah works at a major food brand, managing nature-related disclosures for their agricultural supply chains. She’s constantly fighting for budget, trying to prove to the CFO that sustainability isn’t just a “nice-to-have,” and drowning in consultant reports that cost a fortune and tell her almost nothing actionable. When regulators ask for TNFD compliance, she needs real data, not hand-wavy estimates. She’s smart, overworked, and acutely aware that her job exists in that awkward space between regulatory necessity and executive skepticism.

North star scenario: It’s Q4, and Sarah needs to submit her company’s first TNFD report in three months. She logs into the platform, selects three representative farms from her company’s supply chains (a tomato farm in Southern Europe, a coffee farm in Colombia, a cocoa farm in West Africa). The system shows her existing data coverage - mostly sparse - and recommends specific data collection strategies for each farm and its surrounding area based on crop type and regulatory requirements. She approves the plan, the corporate food buyer coordinates with suppliers, and eDNA surveys plus remote sensing get scheduled. Two months later, she downloads a compliance-ready report showing biodiversity dependencies and impacts, complete with audit trails and modelled intervention scenarios. She presents it to the board. The CFO asks, “Will this actually reduce our supply chain risk?” For the first time, she can say yes and point to specific interventions already underway.

Rajesh the Risk-Mitigator (Corporate Food Buyer)

Rajesh sources raw materials from hundreds of farms across multiple continents. He’s seen supply chain disruptions from droughts, floods, and degraded soils that no longer produce viable yields. His bonus depends on keeping costs stable and ensuring reliable supply, but he’s also under pressure to hit sustainability targets that his company announced to shareholders. He can see these risks mounting, but he’s a procurement expert, not an ecological one - he doesn’t have the knowledge to mitigate them proactively, and by the time they show up in his numbers it’s already too late.

North star scenario: Rajesh gets an alert from the platform: one of his tomato suppliers in Southern Europe shows declining biodiversity metrics and increasing pesticide dependency. The system flags this as a medium-term supply risk - if current trends continue, yields will likely drop 15-20% within three years. It recommends a small pilot with 2 farms to test integrated pest management practices, funded as part of the company’s sustainable sourcing budget. The cost: €15K. The projected ROI: reduced supply risk, improved sustainability metrics for reporting, and potential premium pricing for regeneratively-grown tomatoes. Rajesh greenlights it. Six months later, those 2 farms show measurable improvements. He uses the early results to secure budget for expanding the program and builds it into his pitch for the brand’s sustainable sourcing commitments.

Amara the Ecosystem Whisperer (The One-Woman Consultancy)

Amara is an independent agronomist advising 30 farms across her region. She’s passionate about her work and prides herself on staying ahead of trends. She knows integrated pest management is the future, and her farmer clients are starting to ask about biodiversity and regenerative practices. But she doesn’t have the tools or expertise to offer sophisticated ecological advice - she can recommend crop rotations and fertiliser schedules, but she can’t interpret eDNA results or model predator-prey dynamics. Her competitors at larger consultancies are starting to offer these services, and she’s worried about losing clients.

North star scenario: Amara subscribes to NatureBounds’s agronomist tier. She doesn’t pay for bespoke data collection for her clients’ farms - that would be prohibitively expensive - but she gets access to regional biodiversity data aggregated from corporate surveys, combined with models calibrated on field surveys. Before visiting Elena’s strawberry farm, she pulls up the platform: bioacoustic monitoring from nearby corporate-monitored farms reveals low pollinator activity, with wild bee populations particularly sparse. Remote sensing shows Elena’s specific field layouts, noting a similar lack of pollinator-supporting habitats. Amara connects this to what she knows about Elena’s crop rotations - strawberries alternating with fallow periods. She designs a wildflower planting schedule: native species timed to bloom during fallow periods, supporting pollinators when they need it most without competing with strawberries at harvest. When she arrives, she’s ready with a compelling story backed by data. Elena implements it. The next season sees 12% yield improvement. Amara rolls out similar insights across her client base, becoming known as the agronomist who bridges traditional practice with biodiversity science.

António the Farmer (Multi-Generational Farmer on Thin Margins)

António’s 200-hectare farm has been in his family for generations. He cares deeply about the land - it’s his legacy - but he’s also pragmatic. Pesticide costs have tripled in the past decade. Fertiliser prices are volatile. Drought years are becoming more frequent. He’s heard about “regenerative agriculture” and “biodiversity,” but he doesn’t have thousands of Euros to spend on consultants telling him to plant wildflowers. He’ll listen if someone can show him how to cut costs or get better prices, but he’s been burned before by tech companies selling silver bullets that don’t work in real farming conditions.

North star scenario: António doesn’t pay for NatureBound - the corporate buyer funds both the data collection and his agronomist’s platform access as part of their sustainable sourcing program. His agronomist shows up one day with something new: a detailed analysis of his fields on the NatureBound platform showing low predator-to-pest ratios. The recommendation is specific: plant dill and fennel along his field margins, and consider releasing ladybirds next season. The intervention cost is minimal, also subsidised by the corporate buyer. António is skeptical but figures he has nothing to lose. The next season, his aphid problems are noticeably better, and he cuts his pesticide costs by 30%. The agronomist shows him the biodiversity monitoring data proving the improvement. António remains wary of tech people selling silver bullets - most recently that curly-haired guy Londoner in the Arc’teryx jacket - but he trusts results he can see in his bank account. He signs up for the next phase of the program.

How These Personas Connect

These personas don’t exist in isolation - they’re interconnected through shared data and aligned incentives. Consider António’s intervention from his scenario: when his corporate buyer funds eDNA surveys and bioacoustics to fulfil their TNFD reporting obligations, the platform identifies low ladybird populations and recommends a planting schedule to attract them. António gets a 30% reduction in pesticide costs. Sarah gets biodiversity metrics showing measurable improvement for her compliance report. Rajesh de-risks his tomato supply chain. And Amara gains regional biodiversity data she can leverage for her other clients in the area. The same data collection creates compounding value across all four personas, turning compliance requirements into on-the-ground ecological and economic wins.

Turning Users Into Superheroes

This was the part that excited me most: we weren’t just building a data platform, we were building a product that would turn our users into heroes in their domains.

Imagine Amara walking into a farmer’s field and, within minutes, connecting her deep agronomic expertise to ecosystem-level data that would normally require a team of specialists to collect and analyse. She’d become the agronomist that farmers call first, the one who “just gets it” in ways her competitors can’t match. Her reputation would spread - not because the platform replaced her expertise, but because it amplified what she already knew, letting her see patterns and connections that were always there but previously invisible.

Or Sarah presenting to her board with a story that actually lands: “Last year, we invested €500K in biodiversity monitoring across our tomato supply chain. We identified three high-risk regions. We intervened with targeted programs. This year, those regions show 25% improvement in ecosystem health metrics, pesticide use is down 18%, and we’ve reduced our supply chain risk by a quantifiable margin. Here’s the data, here’s the trajectory, here are the farmers who can testify to the results.” The CFO leans back, impressed. Sarah just became the sustainability officer who delivers business outcomes, not just compliance paperwork.

Rajesh stops being the buyer who reacts to supply chain crises and becomes the strategist who prevents them. He spots the warning signs two years before his competitors do. He invests early in farmer support programs that look like altruism but are actually brilliant risk mitigation. His CEO presents him as an example of “how we think long-term about supply chain resilience” in the next earnings call.

António becomes a pioneer in his region. The data backing his results gives him credibility to push boundaries his neighbors are still hesitant to cross. Premium brands start approaching him, willing to pay 15% more for demonstrably regenerative practices. He gets invited to speak at agricultural conferences - not as someone who was “taught” about biodiversity, but as a farmer proving it works economically. His kids see him leading the future of farming, not clinging to the past, and the farm they weren’t sure about inheriting suddenly looks like an operation worth building on.

Why This Matters

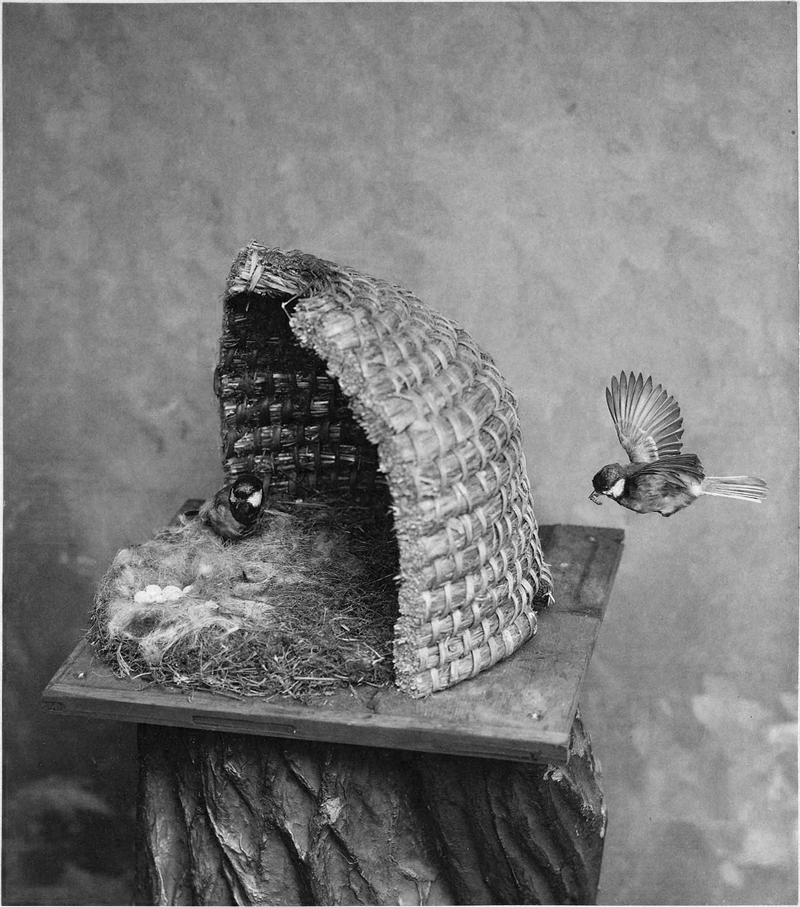

The example above - aphids and ladybirds - is straightforward because it’s a well-understood relationship. A single ladybird can eat 50+ aphids per day. Their larvae are even more voracious. This is textbook biological pest control, and farmers have known about it for generations.

But most ecological relationships are far more complex and context-dependent. The role of bats in controlling crop pests varies by region, crop type, surrounding landscape, and even time of year. The interaction between soil microbiome health and plant resilience to drought involves thousands of species and chemical pathways. The impact of hedgerow placement on pollinator abundance depends on flower timing, connectivity to other habitats, and pesticide drift patterns.

These insights require deep familiarity with multiple data sources and the ability to collect them cost-effectively. No individual agronomist can be expected to master soil biochemistry, geospatial analysis, eDNA interpretation, and crop science. But a platform that interlaces these data sources and applies specialised models can surface these insights at scale.

Observability for Nature

The platform wasn’t just about data integration. It was about giving already-capable people superpowers in their daily work - letting the skilled agronomist punch above their weight, helping the strategic CSO deliver measurable impact, enabling the savvy buyer to act on foresight rather than hindsight, and making the pragmatic farmer prosperous. It was about creating a feedback loop where doing the right thing for nature also made you better at your job, more respected by your peers, and more successful in your career.

That was the vision: make the invisible visible, make the complex actionable, and empower capable people to become the heroes their ecosystems desperately need. We might call this observability for nature - “getting the right information at the right time into the hands of the people who have the ability and responsibility to do the right thing”.

But every product thesis has its antithesis. North star scenarios aren’t truth - they’re informed hypotheses we hold tentatively, until we learn they’re wrong, at which point we revise or discard them. The real question isn’t whether the vision was compelling, but whether it was valid.

In Part 2: Testing the Thesis we explore some of the questions that remain open. Questions that might disprove our entire product thesis once theory meets reality.

- Thanks to months of therapy.

- Hey, that's me!

- To quote Charity Majors and Honeycomb