I’d caution anyone taking management advice from me to keep in mind that I have no idea what I’m doing. I’m just figuring this out as I go along.

With that in mind, I’d suggest you treat this post as anecdotal observations on managing distributed teams, rather than advice on how to do it well.

This post is part of the Distributed by Design essay, which begins with Remote isn’t Distributed, describing what I learned over two and a half years as an individual contributer and manager on a distributed team at Elastic.

Part III: On Managing Distributed Teams

As an Engineering Manager, I believe I can sum up the responsibility of my role as one goal - to leave my team better than I found them.

Whether the team is co-located, distributed, or anything in between, the role is the same: help the team communicate, build products, and support each other’s growth better today than they did yesterday.

When I chose to join a distributed team I did so as an individual contributer, rather than a manager, and I did so as I was worried I might not have the experience required to manage such a team. It didn’t take me long to learn that the Venn-diagram of skills required to manage co-located teams and distributed teams is pretty much a perfect circle.

The tensions and dynamics might be different, but if you are a good manager of a co-located team, then there shouldn’t be any reason to fear managing distributed teams.

On Being Remote in a Distributed Environment

In the first part of this essay we discussed why asynchronous communication is a priority for distributed teams, and the system we have put in place to encourage, or even enforce, its practice.

But what if your team is not distribted, but rather merely remote?

Should asynchronicity still be a priority?

Many teams have asked themselves this question over the past two years, as co-located teams turn to remote work, remaining in the same timezone as they were before. Interestingly, teams at distributed companies like Elastic have also found themselves grappling with this, as many of them are clustered around similar timezones, essentially making them remote rather than distributed.

To tackle this dilemma, we should begin by asking the most obvious question: why wouldn’t you make asynchronicity a priority?

In Part II we saw some of the benefits of asynchronous work, but there are undeniable downsides, such as slower feedback cycles and I wouldn’t hold it against remote teams that chose to side steps these by leaning into synchronous communication.

This is a question I’ve discussed with many Engineering Managers over the past couple of years, and I’ve begun to notice a wind change. More and more teams are beginning to notice downsides to their synchronous work, as these become more pronounced by their transition to remote work. Interactions that once worked face-to-face, don’t work as well over Zoom, and decisions made through ephemeral, and often siloed, instant messaging don’t permeate through the team as they once did.

This leads us to a conflict - on the one hand, asynchronous has obvious downsides, but once you lose the high-frequency communication inherent to co-located teams, it turns out synchronous communication has some serious drawbacks as well.

Many remote teams grapple with this question and, as an engineering manager, you find yourself asking whether your efforts are best spent coaching your team at asynchronous communication, or whether you’re better off focusing on their synchronous communication challenges?

If I were to manage an isolated team, whose product is self-contained, owned, and operated by them, then I could definitely consider deprioritising the goal of adopting asynchronous communication. But I don’t.

My teams aren’t just spread out across timezones themselves but need to collaborate closely with dozens of other teams, who are themselves distributed and spread out across many timezones. To me, deprioritising asynchronousity would mean my team is likely to struggle to collaborate both internally and across to other teams. They will inevitably find themselves having to attend synchronous meetings in order to align on technical challenges, make decisions, keep each other up to date, and more.

This is a burden my teams and I have chosen not to incur, but each team has to make this decision for themselves.

Buy-In for Asynchronicity Isn’t Always Enough

Teams aren’t always aware of the nuanced distinction between remote and distributed, and as a result, they often require coaching to keep these practices on track.

I find it’s easy for remote teams to gravitate back to the communication skills they acquired over the years on their former co-located teams, leaning heavily into instant messaging and ephemeral decision making. This shouldn’t be surprising given that humans are socialised to communicate synchronously, and given the added friction caused by asynchronous communication. In fact, I believe it’s a perfectly normal example for people following the path of least resistence, falling back to these old habits.

As an Engineering Manager it isn’t uncommon to find yourself having to coach your team away from the path of least resistance, but this is always hard, which raises the question: what reason might we have to choose to add friction into our team’s ability to communicate? This seems counter-intuitive, to say the least.

There is only one good reason I can give you, which is that you are adding friction in order to address another, more harmful, source of friction. So it all boils down to one question: is the friction caused by synchronous communication worse than the friction caused by asynchronous communication?

For a distributed team, the symptoms of the friction caused by synchronous communication are usually easy to spot.

The most common is that sync-up meetings, especially those lacking an agenda, tend to creep into team calendars. Every such meeting becomes an anchor that has to be dropped somewhere, and the more anchors the team drops in their calendar, the less freedom individuals have to fit work around their life, which is likely to come up in your coaching sessions.

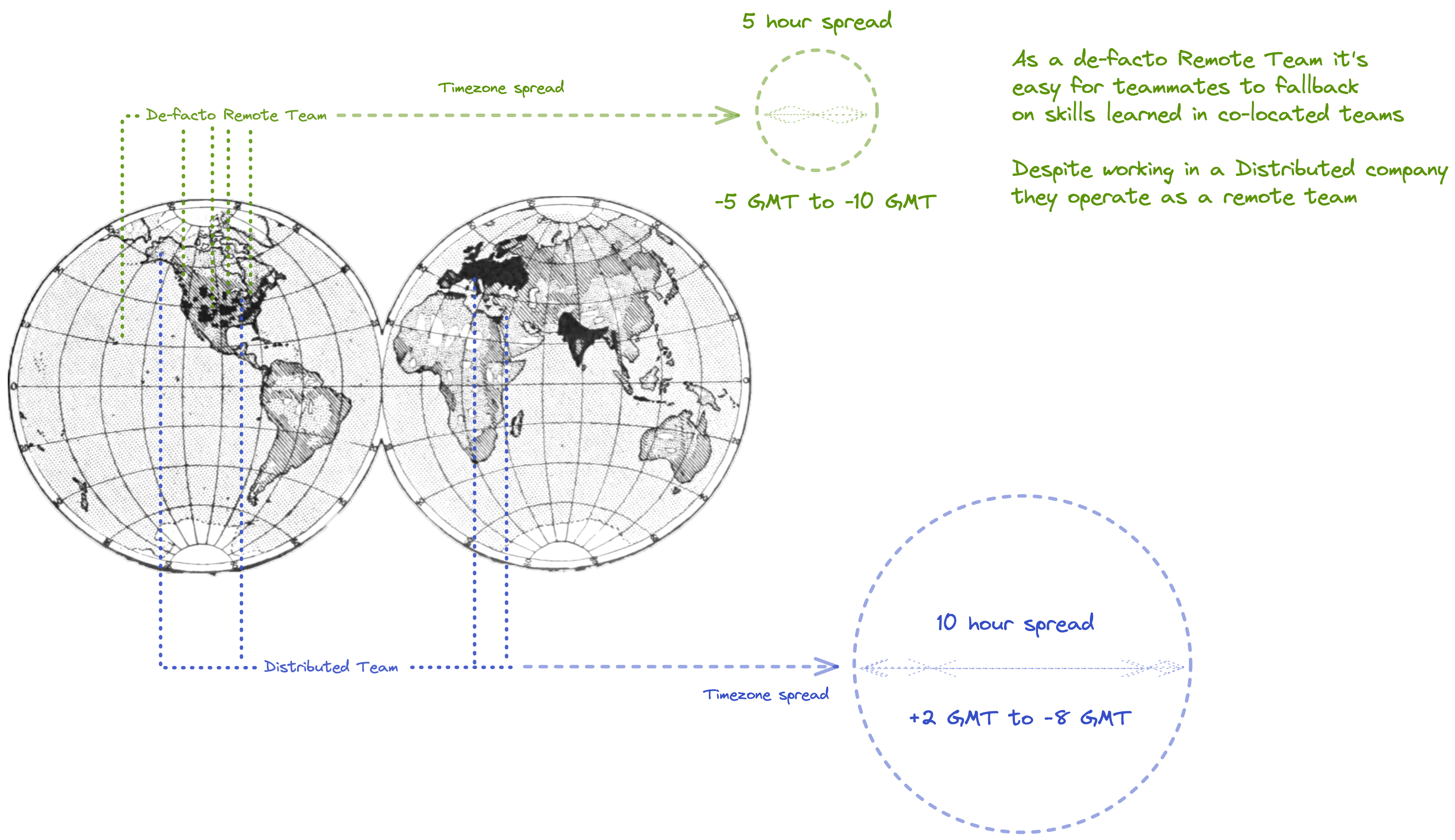

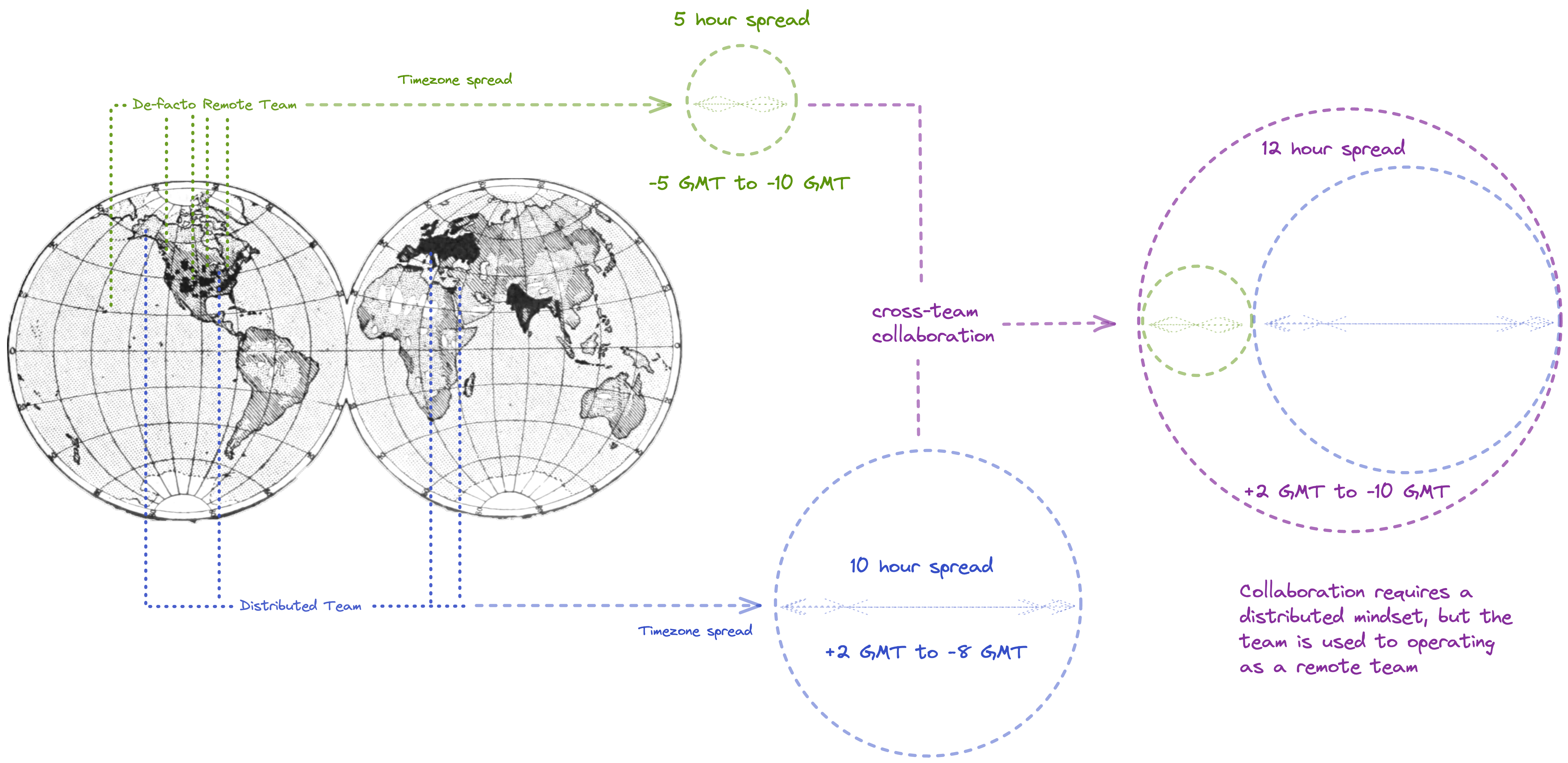

In addition, cross-team collaboration, especially when alignment on a change that spans multiple teams is required, tends to become hard. An interesting nuance, that often indicates an over-reliance on synchronous communication, is that the wider the timezone spread of the different teams is, the harder this cross-team collaboration becomes.

In the following diagram, a remote team for whom the widest timezone gap is 5 hours, can easily rely on synchronous means to collaborate effectively. But the moment this team has to collaborate with a distributed team, for whom the timezone spread is 10 hours, they now have to collaborate in different reality altogether. Though they might be a high-performing team when operating within 5 hours of each other, they are now part of a team operating across 12 hours, and their practices may no longer allow them to collaborate effectively.

Luckily for me, prioritising async is easier than it would be for most, as Elastic has already set such a strong baseline for my teams, but it can still be challenging. Though I might not need to get buy-in for ideas like Home, Dinner, my teammates are only human and can gravitate to old habits as well, especially if they happen to be closer to remote than they are to distributed.

As with any other change you’d like to coach your team into, it’s far better to inspire the team’s buy-in by helping them see the same problems you see, rather than coercing them into it.

My favoured approach to this challenge is to begin by identifying the source of resistance to the change and coach the members of my team to a place where they can see it too, and choose to address these themselves.

Each team is unique, and as their Engineering Manager you are best placed to coach them through a discovery process which concludes, hopefully, at a decision: do we work hard to adopt asynchronous communication, or do we stick with synchronous?

The one piece of advice I can give, having seen how this has played out for several teams, is that most of them struggle to recognise the downsides inherent to synchronous practices. Perhaps this blind spot is caused by the comfort of the familiar, I don’t know, but I have found that the best place to start is to help the team recognise the friction, and its root cause, for themselves. Trust them to figure out the solutions on their own, but your role is to get their buy-in for the effort by helping them recognise that a problem exists and that they can solve it.

On Tracking Performance

In discussing my experience of managing distributed teams, I have noticed an interesting parallel between my teammates’ tendency to follow the path of least resistance, and my own approach to performance tracking.

A member of my team recently told me how they advocated to a friend of theirs on behalf of our team, encouraging them to apply for an open position we’ve been hiring for. They shared with me that their friend asked a question about our distributed team practices, “how do you track people’s performance if you work asynchronously and work-hours aren’t strict?” at which point, my teammate admitted, they realised they couldn’t answer that question. My teammate wasn’t actually sure how I tracked their performance, which was itself, a revelation for us both.

I’ll admit that I had to pause for a moment, but it quickly clicked into place:

“Well, I don’t. Not directly, at least.”, I replied, “But I can say that I can tell exactly who is performing well, and who needs coaching, and I do so via far more valuable proxies than work-hours.”

I have realised that, in the past, in lieu of a better signal, I would at times fall back to using work hours as a proxy for whether a teammate’s effort is meeting expectations. This is, obviously, a bad habit, but it is important to recognise that it is also the path of least resistance for many managers, which is why we take it.

A nice side effect to embracing asynchronous work has been that work-hours are no longer just a bad (and lazy) proxy, but a difficult one to track.

They no longer represent a path of little resistance, but rather a high degree of resistance, due to two obvious reasons:

The first is that tracking work-hours would require you, as a manager, to track work that takes place outside of your own work hours.

The second is that you will find it is impossible to both communicate to your team that they are free to manage their time as they see fit, while also tracking that time. It’s neither feasible nor reasonable.

Instead, performance tracking shifts entirely into the realm of coaching. Learning how to leverage effective 1:1s, working closely with your team to identify performance challenges, providing feedback, discussing their process, and helping them grow.

These skills have been covered by far more experienced leaders than myself, such as Camille Fournier, so I won’t try and advise you on these myself. But the observation I feel might be less obvious is that managing distributed teams forces you to hone these skills.

Ironically, I find it is easier for inexperienced managers to hide in plain sight when they inhabit the same space as their team. Once you turn remote, and especially distributed, you can no longer rely on the rich signal you get from constantly observing your team. You have to learn to see by other means, and I have found no better means than connecting with my teammates and peers through conversation.

A Note with Regards to Overwork

My favourite nuance to this has been that I can no longer use work-hours as a proxy for overwork, either.

In the past, if I were to spot a teammate working out of hours, I’d assume they were overworking and address this concern accordingly. Earlier on as a manager on a distributed team, I began to notice this practice becoming harder, as I had to familiarise myself with each individual’s workhours across timezones. This is neither scalable nor effective.

The aha-moment for me was the moment I realised that a member of my team would regularly take breaks during the day, going for a walk with their partner, or an afternoon cycle in the woods. They would then make up those hours in the evenings, or weekends, and on observation I realised - this is exactly what Home, Dinner and asynchronous work are about: freeing the members of our team to manage their time as they see fit while still being an effective team.

This means I can no longer use workhours as a proxy for anything, whether it’s tracking performance or overwork. Either way, I need a better metric, and that’s where effective feedback and coaching is required.

- Which is why we've seen many companies shift to surveillance software over the past two years, and though I try not to judge, if there is one hill I'm willing to die on it is that managers who resort to surveilling their teammates are lacking some core management competencies.